2 Comments

Before the introduction of modern medicine, the Kookums (Grandmothers) were the traditional keepers of knowledge of herbal plant remedies. They were midwives for the Anishinaabe community and had an understanding of a whole range of medicines that could cure illness that their families might encounter. This knowledge was not exclusive, but was something that was shared between First Nations women and their children, including the Métis.

This is why we must honor our grandmothers and our mothers, for they hold the wisdom and knowledge of generations of mothers and grandmothers before them. Once, a long time ago, a young man lived with his wife and children in a remote area near a large lake. He would go hunting every day and would return with all sorts of game.

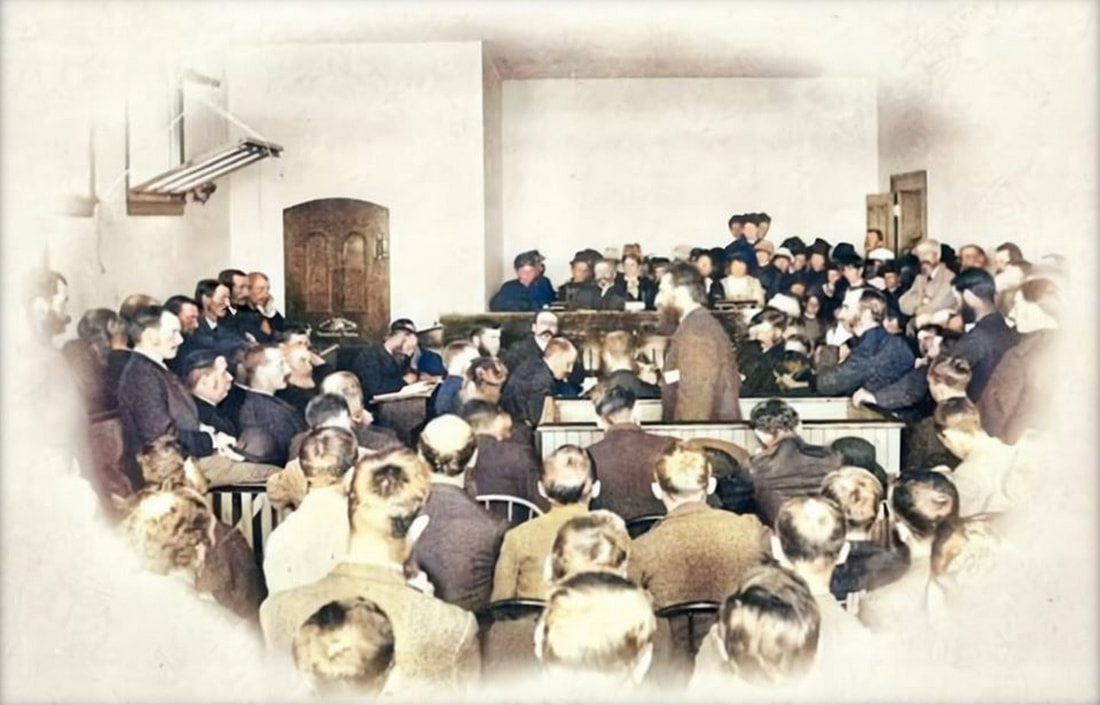

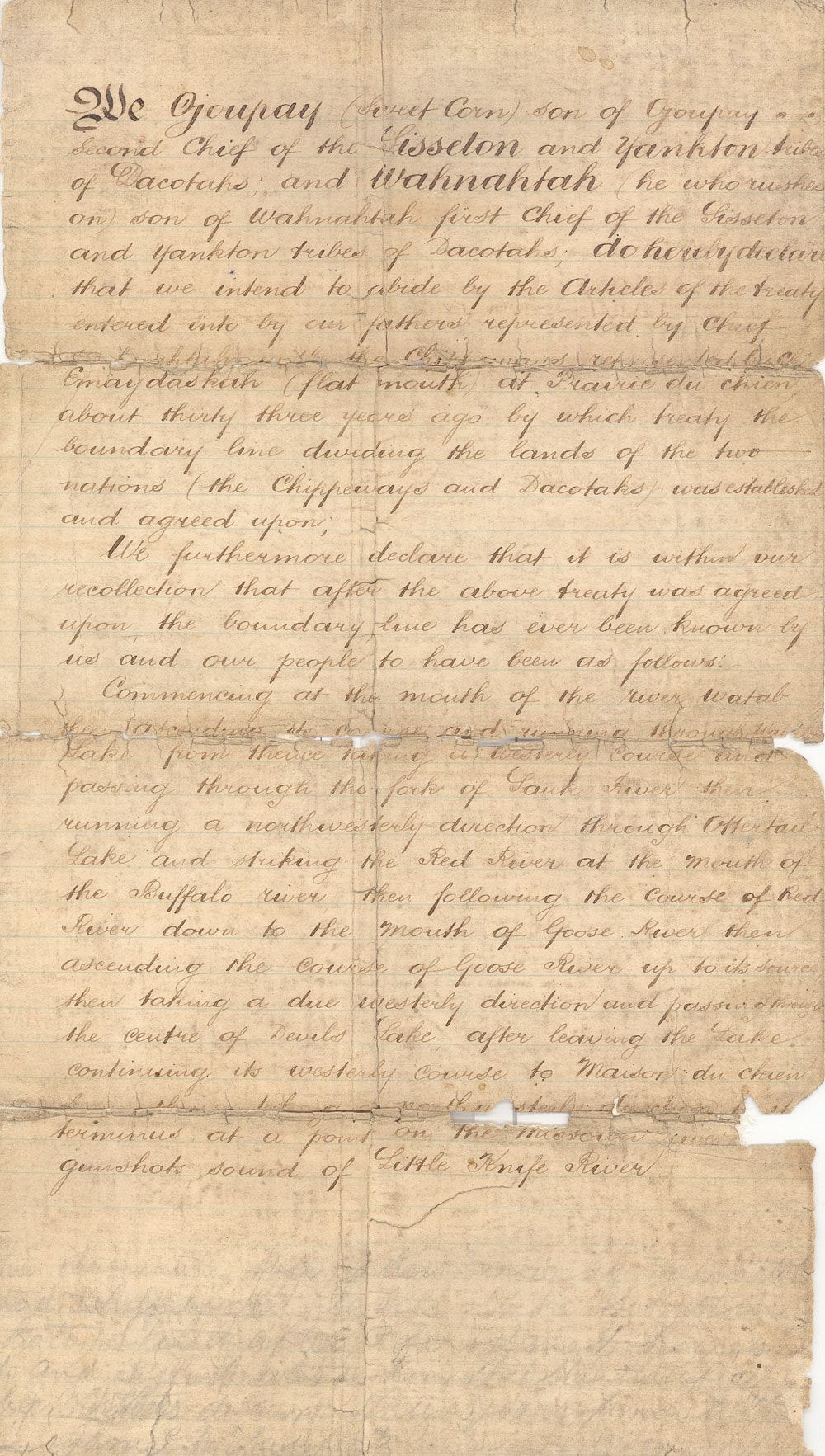

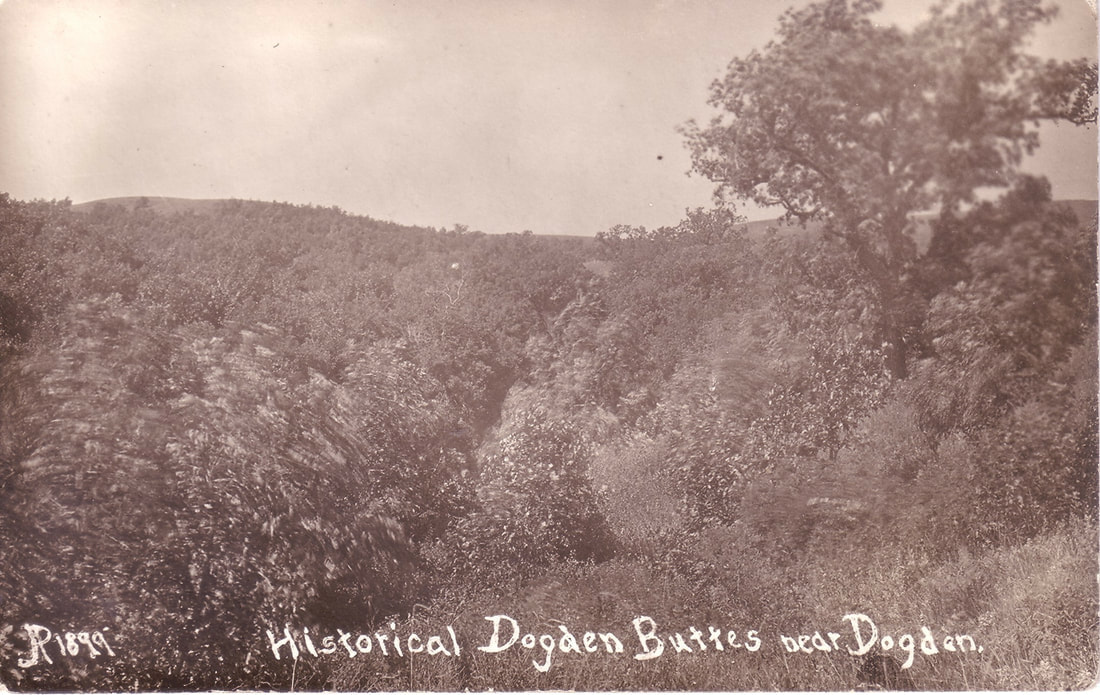

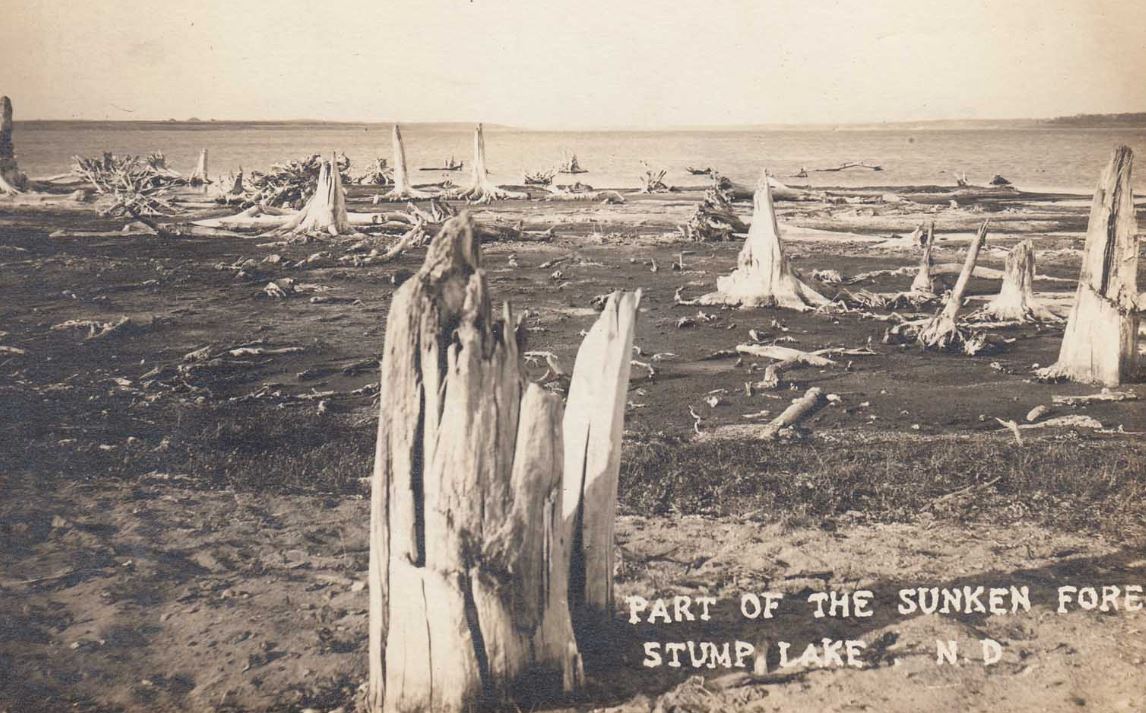

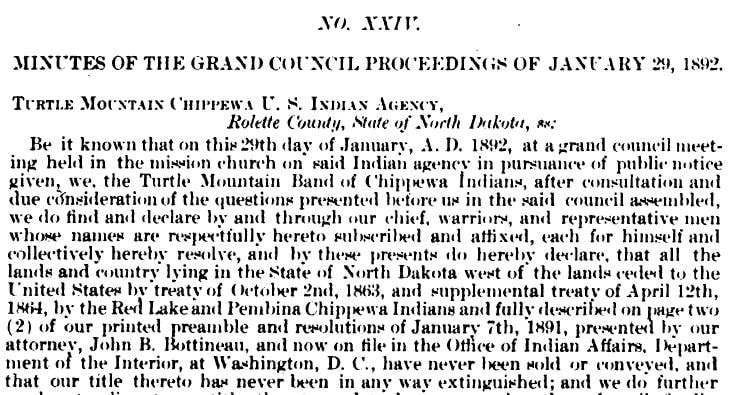

During one of his hunting trips, he saw a fat squirrel and shot it with his arrow. As he was going to pick it up, he noticed a small man about two feet tall coming from around a tree. The small man – a memegwesi – said to the hunter, “Beshwaji! I was stalking that squirrel for my prey. You stole it from me, but I do not hold a grudge for that. Nonetheless, could you give it to me so that I might feed my family?” The young hunter agreed, and he and the memegwesi decided to camp together, and they both had a great time sharing stories and boasting about their hunting prowess. After a successful time hunting, the young man asked the memegwesi if he would like to bring his family and live with him in his lodge. They could be brothers and always hunt together. The memegwesi agreed. The memegwesi had a wife and two young children: one was no bigger than six inches high, the other about one foot high. They came to the lodge of the young hunter and took up house in a corner of it. Every day the young man and the memegwesi would go out hunting. The young man might kill a deer or a moose, and the memegwesi would kill squirrels and rabbits. They had good luck every day, and when they would go home the memegwesi’s wife would help him bring his squirrel or rabbit inside and would cook it up for him, and the young man’s wife would cook his deer. The memegwesi’s wife would scrape the hides of his small animals and made him wonderful clothing. This little memegwesi had powers to do certain tricks, and he would entertain his family and the family of his young friend through the long winter nights and he would bring luck to his friend. They were all very happy in their friendship. One day during a particularly warm spring, just after they had made maple sugar together, the memegwesi told his young friend, “We are leaving now. We have had a good time living with you and thank you for always being my friend. I wish you good luck every day and to be happy all your life.” The memegwesi family gathered up their things and disappeared. Until his dying day, the young hunter and his family always had good luck thanks to his memegwesi friend’s blessings. By Kade Ferris One of the most reliable sources for defining the territory of the Pembina/Turtle Mountain Ojibwe in what is now North Dakota comes from the 1858 peace agreement, forged between the chiefs and headmen of the band and the Sisseton and Yankton Dakota, called the “Sweet Corn Treaty”. The Sweet Corn Treaty sought to establish peace and to define hunting and territorial boundaries so that there was no cause for warfare and so that resources would be shared without animosity. The Sweet Corn Treaty was read into various congressional bills throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, and was later used in the official findings of the Indian Claims Commission. The language of the treaty stated: We, Ojoupay (Sweet Corn, son of Ojoupay), second chief of the Sisseton and Yankton tribes of Dakotas, and Wahnatah (He-who-rushes-on), son of Wahnatah, first chief of the Sisseton and Yankton tribes of Dakotas, do hereby declare that we intend to abide by the articles of the treaty entered into by our fathers, represented by Chief Wahnatah with the Chippewas, represented by Chief Emaydaskah (Flat Mouth) at Prairie du Chine, about thirty-three years ago, by which treaty the boundary line dividing the lands of the two nations (the Chippewas and Dakotas) was established and agreed upon. We further declare that it is within our recollection that after the above treaty was agreed upon the boundary line has ever been known to us and our people to have been as follows: Commencing at the mouth of the River Wahtab, thence ascending its course and running through Lake Wahtab; from thence taking a westerly course and passing through the fork of Sauk River; thence running in a northerly direction through Otter Tail Lake and striking the Red River at the mouth of Buffalo River, thence following the course of the Red River down to the mouth of Goose River, thence ascending the course of Goose River up to its source; then taking the due westerly course and passing through the center of Devils Lake at Poplar Grove; after leaving the lake, continuing its westerly course to Maison du Chine [Dogden Butte]; from thence taking a northwesterly direction to its terminus at a point near the Missouri River within gunshot sound of the Little Knife River." (US Department of Interior 1872). This general territory was later granted congressional acknowledgement in an April 18, 1876, report of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, which after considering a memorial from the Turtle Mountain Chippewa, reported a bill that authorized the setting aside of a reservation for the Turtle Mountain Band. In its report the committee stated: The Turtle Mountain band of Chippewa Indians, and their forefathers for many generations, have inhabited and possessed, as fully and completely as any nation of Indians on this continent have ever possessed any region of country all that tract of land lying within the following boundaries, to wit: On the north by the boundary between the United States and the British possessions; on the east by the Red River of the North: on the south their boundary follows Goose River up the Middle Fork; thence up the head of Middle Fork; thence west-northwest to the junction of Beaver Lodge and Shyenne River; thence up Shyenne River to its headwaters; thence northwest to the headwaters of Little Knife River, a tributary of the Missouri River; and thence due north to the boundary between the United States and the British possessions (Indian Claims Commission 23-315). Just a few years later (September 25, 1880), Superintendent James McLaughlin, agent at the Devils Lake Agency, wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs concerning the plight of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa. He reported that white settlers were trespassing on their lands, and recommended that a reservation be set aside for them. Specifically, Agent McLaughlin reported: Inasmuch as the section of country west of the treaty line of 1863 running from Lake Chicot [Stump Lake] in a line nearly due west by Devils Lake and Dogs Den to the mouth of the Little Knife River on the Missouri, thence north to the "Roche Perce" or Hole in the Rock on the International line, thence east along the International line until its intersection with the treaty line of 1863, which tract is about 80 by 200 in extent, is recognized by all neighboring Indians as belonging to the Pembina and Turtle Mountain Bands of Chippewas, and as the same has never been ceded to the government, and the Indians being desirous to relinquish for a consideration to enable them to commence a life of agriculture, I would respectfully recommend it to the careful consideration of the Department (Indian Claims Commission 72-113). Each of the points mentioned in the above descriptions correspond to a place of importance and/or settlement associated with the Turtle Mountain Chippewa. For example, Stump Lake was the location of the village of Black Duck (Mug-a-dish-ib), a powerful sub-chief of the Ojibwe; Poplar Grove (Graham’s Island) is the location of the village of Chief Little Shell I and was also the location of a Chippewa village attacked by the Dakota in 1852; Dogden Butte was an important hunting and camping area to the Ojibwe (Indian Claims Commission 23-315). References:

United States Indian Claims Commission (ICC) (1970) Before the Indian Claims Commission. Indian Claims Commission Docket 23-315. United States General Printing Office. United States Indian Claims Commission (ICC) (1970) Before the Indian Claims Commission. Indian Claims Commission Docket 72-113. United States General Printing Office. US Congress (Department of Interior) (1872) U.S. Serial Set, Number 4015, 56th Congress, 1st Session, Pages 852 and 853. United States General Printing Office. This is NOT an exhaustive list of everyone who was present at the Grand Council of 1892, but is a list of persons present who had both a listed name and an accompanying "Indian name" listed in the minutes. Most of the names are in either Michif or Ojibwe. No translations are provided and the spellings are probably not entirely accurate.

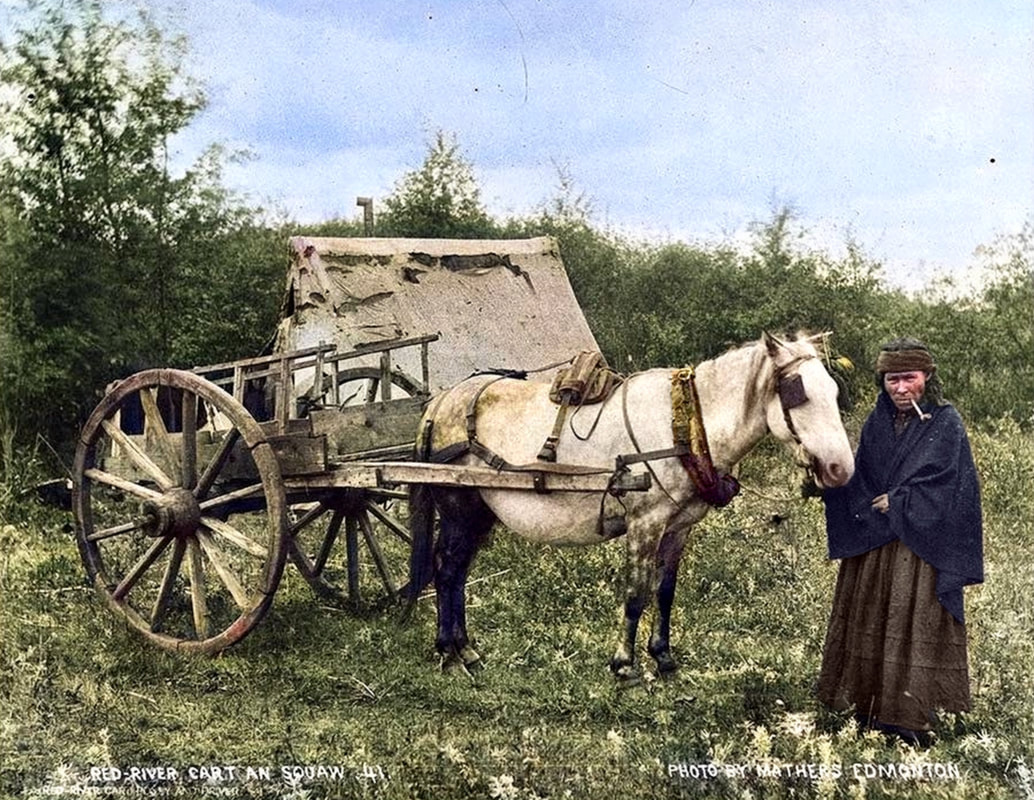

Names from the Minutes of the Grand Council Proceedings of January 29, 1892: Arkee winini (Alexandre Jeanotte, Sr.) Kar tah koo zit (Donald Short) Ping gan (Rimeau Larocque) Chonz (John Hayes) Tchee non (Charles Poitra) Ko tah mash (Modest Poitra) May zha ke gwan abe (Zachari Poitra) Knee croph (Joseph Poitra) Tehee kas son (Henri Poitra) Oza we dject (Bastien Poitra) Sharl lens (Charles Poitra) Lip tchee (Napoleon Poitra) Ohe zan e ke shiz (Theodore Belgarde) Omud diz (Maxim Lefort) Ojib wanice (Galisse St. Arneau) Mayn se daish kung (Alex St. Arneau) Ah zhow e ge shig (St. Pierre Laverdure) Was sarh kaish (Casimere Bouvier) Pip pee shaish (J. Baptiste Jeanotte) Tchoo wan do (Jacob Laviollette) Man ne tous (Albert Laviolette) Mch quah tiss (Stanislas Goslin) Osh ke nar wins (Jaspard Jeanotte, Jr.) Mee shee tay (William John Jeanotte), Nur bay shish (Pierre Jeanotte) Nar may we nini (Louis Richard) Kee yash koo shish (Charles Ross, sr.) To toosh (William Ross) Ah zle day aush (Francois Dauiphinais) Mee gwon (Gaspard Jeanotte, Sr.) Osh kee now (Leon Jeanotte) Mish quom meesh (Alexandre Jeanotte, Jr.) War bish tee gwan (John Frothier) Ine ne wish (Joseph Morriseau) Tcheer Kuhk (Joseph Demarais) In de bay we ne ne (Antoine Gosslin) Nay tow o say (Jonas Azure) Obe sane ge shig (Antoine Azure) Bay bah o nub (Francois Patnaude) Tay banse gay (Samnion Patnaude) Mamais se sip (Alexandre Sayers) Song law (Joseph Sayers) Wid don (Louis Vallee) Kill tchee ozhoop (Pierre Thibert) Kar kar naish (Francios Morin) Pet tchee ton (Joseph Brazeau) Pas ko tail (Star McGillis) Kar kikam mick (Alexander Larocque), Osh kee now wens (Germeie Ladoux) Tchee gus toosh (Kilaface Briere) Ome mee (Antoine Desjarlais) Tchee kee tam ens (Boniface Parisien) Kin wah tig gons (Patrick Grandbois) Andree shish (Andren Morin) Kih tchee nor bay (Pierre Morin) Osh kin oway (George Frederick) Tah ko shish (Joseph Boneau) Ish quork kee zons (Louis Lenoir) Nap pah kee tche quonish (Pierre Laverdure) Ls swis (Gabriel Poitra) Watch amush (Xavier Thibert) Ohk kan nish (Jean Baptiste Langan), See see dje won ( Francios Langan) Nap pe win (Charles Laviolette) Tcho pee chee (Oliver Larocque) Lil ley (James Williams) Kakinotoop (Frank Demery) Kay bay o ge mah (Joseph Lafournaise) Obe quod aince (Patien Lafournaise) Pah gwav cub (John Azure) Kin wahte go zee (Isidore Grandbois) View gar song (Joseph Gladue) Weeks quoy (Francois Fournier) Wee we yarn (Norbert Fournier, Jr.) Boin ace inah (Alexis Malataire) Mah tchar min (Joeph Azure) Ke way ke new (Benjamin Azure) Tehee kee tarn (Ignacieus Parisien) Sharl gardee (Charles Beston) Mih tigonish (Laurent Duchien) Sharl loo (Charle Patenaude) Nub un ay gar bou (Michel Davis) Tchee quan (Charles Gladue) Tche quon ence (Charles Gladue, Sr.) Pah tee no de we (Corbet Patnaude) Nud bay shish (Norbert Landry) Mush kar o say (Alexis Zatste) Pat tee tit (Jean Baptiste Bercier) Tchee moy eez (Moise Azure) Kay kay quosh (Jean Baptiste Martel) Tchee zanvalee (Jean Baptiste Valley) Su serde surrett (Gabriel Portra) War be zee (Frederick Swain) Cour cur (Joseph Poitra) Pah dway we dung (Louis Lenoir) Kih tche inini (Michel Lenoir) Osh kah way (Abrah Honore) Pug un auhk (Alexandre Davis) Karn nar dah (Antoine Unean) War be zeens (Francis Swain) Peep pe shaish (Francois Jeanotte) Ne gon e be nais (James Azure) Sharl la grace (Charles Page) Mar pay shish (Jeremie Malaterre) Fo toosh (Antoine Azure) Peyay shish (Charles Azure) Pin dar nash (Francis Honore) Sharllens (Charles Azure) Arke wen zee (Louis Decoteau) Nee kar nis (Moise Wallette) Me she town ish (Berard Ah gah quaye) Mih keenoo tens (Francis Mcleod) Wisarko day inini (Augustin LeFort) Abrah mish (Abram Boyer) Barnah bee (Theophil Martin) Zoo may (Alex Azure) Pooh yar kar (St. Pierre Gladue) Annee ko she zam (Corbette Bereier) Sewonk kon (Jean Louis Fayant) Mar yarm mons (Louis Lafontain) Min nah gay (Pierre Lafontain) Kee tar kiss (William Fayant) Bon om (Antoine Bouvier) Par pee tchee (Hernias Demontigny) Batees shish (Jean B. Valley) An neep (Louis Decoteau) Ne mi gwan nis (Zachari Malaterre) Oke mar shish (Onezin Houle) Tchee zo zay (Joseph Laverdure) Tchee William (William Davis) Tchee Davis (Leandre Davis) Mung ge sheegan (Jerome Davis) Sas swain (Henri Poitra), By Kade Ferris In a Letter from the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, accompanying the Annual Report of the Board of Regents for the year 1879, a very vivid description of the Metis people was given. This description discussed such issues as the Metis homeland and settlements, the tribes from which the Metis derived their Indian blood and kinship, their housing, mode of dress, the linguistic aspects of the Metis people, and some of the family names of the Metis Nation. A highly detailed document, it provides a very good basis for additional research into the Metis people. METIS POPULATION In discussing homeland and community, the document states that the province of Manitoba, extending from the boundary line to Lake Winnipeg, is the great center of the Metis homeland. In this area, strong communities were concentrated around Winnipeg in places such as Fort Garry, St. Boniface, St. Vital, St. Norbert, St. Agatha, St. Anne, St. Charles, and St. Francis Xavier (or Grantstown). The population estimate for the area was place around 6,500 people, with an additional 500 living in various area around the shores of Lake Winnipeg, Lake Manitoba, and in the Rainy Lake district of Ontario. In the Saskatchewan district, the letter stated that many of the settlements were scattered along the Saskatchewan River, clustering around trading posts, and in Alberta settlements were most numerous along the base of the Rocky Mountains in places such as Fort Edmonton, St. Albert, and St. Anne, with the number residing in that area totaling around 2,500 Metis. At little Slave Lake (and vicinity) an additional 500 Metis were living, and other large concentrations include about 500 souls in the vicinity of Lac Labiche, 300 at Peace River and vicinity, and varying numbers of scattered families ranging as far north as the Great Slave Lake. Other places with concentrations of Metis included Turtle Mountain in what is now North Dakota, Wood Mountains in Saskatchewan, Cypress Hills in Saskatchewan and Alberta, Milk River and French Creek, Montana, and additional groups in British Columbia at the Fraser and Okanagan Rivers, Lakes Kamloops, Babine, and Stuart. The document estimated that over 33,000 Metis were living in the Canadian northwest. The letter also made a hypothetical guess that if the French-descended families outside the Metis homeland, stated to be “tainted with Indian blood”, residing in places such as eastern Canada, Illinois, and Missouri were included, perhaps an additional 7,000 people might be added to this total. BLOOD AND KINSHIP The letter also discussed some of the tribes to which the Metis were related by blood and kinship. These tribes included early admixture with Montagnais, Ottawa, and Huron, with limited mixing with Iroquois and Ottawa tribes. The majority of Metis, it states, derived their bloodlines from the Ojibwe, Cree, and Assiniboine, with minor influence of Dakota Sioux. Those Metis hailing from Saskatchewan were mostly of Cree extraction, Metis hailing from around Pembina, St. Joseph, Winnipeg, Rainy River, the Red River were mainly of Ojibwe and Saulteaux blood, while the Metis of Alberta northward to the Great Slave Lake were exclusively of Cree origin. The Metis who possessed Iroquois blood were small in number and hailed from around Lake Winnipeg and at areas near the Rocky Mountains. Of the other tribal bloodlines, a small proportion of Blackfeet and Montagnais Metis were known to be operating near the base of the Rocky Mountains; the Blackfeet Metis living in the south and the Metis with Montagnais blood living to the north with the Cree derived Metis. Metis with Assiniboine ties were more common in southern Manitoba, and northern North Dakota, and some groups with Ojibwe, Assiniboine, and Dakota Sioux blood were operating in the Red River and Devil’s Lake region of North Dakota. There were some Gros Ventre and Flathead associated Metis in Montana, with some Cree and Ojibwe Metis there as well, mostly in the Milk River region. HOUSING AND DRESS In terms of housing, the letter states that the average Metis house—especially those typical along the Red River—were small, one-story log structures with one, sometimes two or three rooms, and very sparsely furnished. In one corner of the principal room, the bed of the heads of the family were usually placed. An open fire-place, constructed to be tall and narrow—so as to accommodate logs placed upright—was along the middle of one of the walls. If possible, a table, dresser, and a few boxes serving duty as storage and as chairs, constituted the furniture. Almost all activities would happen in this room, including eating and sleeping. In their dress the Metis, it was noted, had a remarkable fondness for finery and gaudy attire. The Manitoba Metis men usually wore a blue overcoat (or capote) with conspicuous brass buttons, black or drab corduroy trousers, and a belt or sash around their waist, with garter leggings and moccasins. Their clothes would usually be variously adorned with colored fringes, scallops, and beads. Younger men might wear leggings made of blue cloth, which would extend to the knee, below which was tied with a gaudy garter with heavy bead work running down the outer seam. The Metis women generally dressed in a black gown with a black shawl thrown over the head, while young girls often wore a colored shawl about their shoulders and a showy bonnet or kerchief upon the head. The women loved the color scarlet and prized gaudy ribbons and jewelry. LANGUAGES

It was noted that the Metis generally spoke several languages, including one or more Indian dialects, French-patois, and often English. Most of the Metis residing in the United States could speak and understand English and used it when conversing with white men, but spoke their native language between themselves. Similarly, the Metis at Red River, Saskatchewan, and Milk River settlements, only spoke English when conversing with white men. In terms of Indian languages, the Metis around Rainy River westward spoke mostly Ojibwe, while the further west one went Cree became the language of choice. Many of the Metis in what is now North Dakota could speak Ojibwe, Dakota Sioux, and Cree, while in other places the dialect of the tribe from which they originated was spoke (e.g. Gros Ventre, Assiniboine, etc.) While French is understood by the Metis, the French is a patois that is not comprehensive but contains a large number of peculiar words and expressions grown out of the character of the land they live in, and their mode of life they live. Their pronunciation is generally understood by a Frenchman in spite of its difference, but the French spoke by the white man is not readily understood by the average Metis. SOME FAMILY NAMES The names of Metis, it was stated, were primarily derived from the original French Canadian families from the east. Some of the names found around the Lakes in Manitoba included: Bonaventure, Saint-Arnaud, De Montigny, Saint-Cyr, Saint-Germain, La Morandiére, and La Ronde. Farther north, names included: De Mandeville, Saint-George, Laporte, Saint-Luc, Racette, Lépinais, and De Charlais [Desjarlais]. Among the most common family names at Red River were: Boucher, Bourassa, Boyer, Cadotte, Capelette, Carrière, Charette, Delorme, Deschambeau, Dumas, Flamand, Garneau, Gosselin, Grand Bois, Gaudry, Goulet, Hupé, Larocque, Lucier, Lagemodière, Laderoute, Lepuie, Laframbaise, Letendre, Morin, Montreuil, Martel, Normand, Rinville, and Villebrun. Other common names included: Saint-André, Bellanger, Bonneau, Boucher, Baudry, Biron, Chevalier, Cadotte, Chenier, Deschamps, Frichette, Giroux, Gendron, Grondin, Hamelin, Lapierre, Lavallée, Lécuyer, Lévéque, Lusignau, Labutte, Lépine, Mainville, Nolin, Plaute, Pelletier, Perrault, Pilotte, Piquette, Riel, Saintonge, and Thibault. Further west, names like Gregoire, Maison, Lachapelle, Delorme, Vaudal, Lucier, Gervais, and Rondeau could be found. Some Metis names found in Montana included: Asselin, Jaugras, Moriceau, Lade route, Lafontaine, Larose, Lavallée, Poirier, Dupuis, Bisson, Houille, and Carrier. Some of the names found in British Columbia included: Allard, Boucher, Boulanger, Danant, Dionne, Durocher, Falandeau, Gagnou, Giraud, Lacroix, Lafleur, Napoleon, Perault. Some of the names that began with the “La” possibly originated in the wilderness and were not necessarily derived from white fathers. Other names could be found, and any of these names listed above, and others, could be found in and among all Metis communities. Some Scottish and English names were also present, but these are not listed. WORK In terms of work, the Metis could be found in a variety of positions working at trading posts as porters, laborers, and other positions. Many moved goods from place to place in their carts, and some were boatmen. Trading establishments also hired Metis men to serve as trappers and hunters to supply the posts with goods to sell and trade. Estimates are that about 25 percent of Metis were employed this way. Others served as guides and interpreters. The vast majority are hunters who are dependent on the buffalo and work the hide and pemmican trade. Their women are expert in tanning hides and robes. It is said that their bead-work was outstanding and they were very skillful in the ornamentation of furs and buckskin. REFERENCE: Annual Report of the Board of Regions for the year 1879, Smithsonian Institute, Washington: Smithsonian Institute. By Kade Ferris Master fiddler Mike Page was born on June 30, 1939, the son of Jean Baptiste Page and Frances Fayant. One of 14 children, Mike and his family farmed and lived west of Belcourt and northwest of the St. Anthony's Catholic Church in the foothills of the Turtle Mountains. Jean Baptiste was a fiddler and passed down his skills to his sons - including Mike - and over his lifetime Mike became a well-known and respected Metis fiddler. Mike was featured on the Smithsonian Folkways CD Plains Chippewa/Metis Music From the Turtle Mountains (1984) and was also featured in the documentary film, Medicine Fiddle (1992). On June 11, 2010, Mike was inducted into the Fiddlers Hall of Fame at the International Peace Gardens. Mike enjoyed spending time with his children and grandchildren, visiting and telling stories. He loved history and never stopped learning. Mike married Dorothy Azure on November 25, 1965, and together they raised 5 children, 13 grandchildren, and 5 great-grandchildren. Mike passed away on Monday, January 25, 2016, at Belcourt hospital. Story by Kade Ferris On a lonely river, in a small village, once lived a man named Gizhiiyaanimad and his wife Baashkaabigwanii. They had three children: two sons, Bizhiins and Gekek, a daughter named Anangokwe. The children grew up to be fine people and one day the daughter married a man who came to her father and offered many furs and gifts for her. Her father accepted these, even though the man, Wiiyagasenh was known to be a bad man, and even though Anangokwe did not like him. Sadly, Anangokwe went away with her new husband and soon found he was a very jealous man who often hit her for no reason other than he enjoyed being cruel. One day, Wiiyagasenh decided to go hunting in a very remote area that was quite a distance away from camp. Gizhiiyaanimad and Baashkaabigwanii knew that Wiiyagasenh was often brutal and abusive to Anangokwe, and they were afraid that he might kill her while out hunting while she was alone with him. They decided to send Bizhiins along with under the pretense of ‘helping’ his brother in law. The two men and the Anangokwe camped near a lake that had lots of nesting ducks in the rushes along the shore. They set up camp and took up hunting. When her brother was out hunting by himself, Anangokwe's husband ordered her to bring him a duck egg for breakfast. While down at the shore of the lake, she met a man who said to her “Aniin young lady. What do you want?” Anangokwe responded, “My husband has sent me to get an egg” she answered. He gave her one, which she carried home and set down outside the wigwam. When her husband asked her if she had brought the egg, she told him that she had left it outside. He went out and looked at it, then said very angrily “I don't want a small egg like this! I will surely starve. I want a big one.” Anangokwe returned to the lake and, meeting the same man again, said to him “It is a big egg that my husband wants.” The man smiled and he picked up an egg twice the size of a normal duck egg. He gave her the big egg and she walked back to the camp and again left outside the wigwam. But her husband only became angrier and said, “Stupid woman! This egg is not big enough. Bring me a bigger one” and he hit her across the face. So for the third time she returned to the lake and told the man that her husband was not satisfied. The man took her hand and said, “Young woman. Nothing you can do will satisfy your husband. He only wants to kill you. Remain with me. You must not go home.”

The woman stayed with the man. Her brother returned from his hunting and asked her husband “Where is your wife…my sister?” “I do not know,” the husband answered. After discussing it, Biizhins and Wiiyagasenh followed Anangokwe's tracks to the lake and looked out over the water. Suddenly, Anangokwe rose up from the middle of the lake. She told her brother what had happened. In anger, Bizhiins turned to his brother in law and hit him with his club, killing him. Anangokwe then said to Bizhiins, “Brother. Return to our parents. You must tell them to come to this lake at the same time as this next year.” Bizhiins told her he would, and he returned to his village and reported this to his parents. Exactly a year later, Gizhiiyaanimad and Baashkaabigwanii came to the lake, and Anangokwe rose from the water. In one arm she was holding a baby girl, and in the other was a baby boy. She said to her parents, “Mother and father. Take these children and raise them. When they grow up let them marry for love and not because of custom. I married the wrong man because if it, and I was miserable.” From that day forward, the people made the decision to take love into consideration when choosing spouses for their sons and daughters. |

AuthorKade M. Ferris, MSc

Archives

June 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed