|

WALHALLA (ST. JOSEPH) A beautifully situated community located in the wooded river valley at the slope of Second Pembina Mountain, Walhalla (or Old St. Joseph) got its start when trader Norman Kittson built a trading post here in 1843 to take advantage of the many Ojibwe and Metis who camped here throughout the year. Antoine B. Gingras, a half-breed trader, also started a post here in 1843. Later, in 1848, Father George Belcourt established a mission here which was called St. Joseph to work with the 50+ families who made this their regular home. In 1851, additional missionaries arrived, and in 1853 the Pembina Belfry, known as the “Angelus Bell”, was relocated to St. Joseph to officially sanctify the mission. The bell is believed to have been brought from Pembina to St. Joseph by Red River cart. By 1860 the settlement had become an important fur trading post, with a population of 1,800—mostly Metis half-breeds and Plains Ojibwe. In 1862 a post office was established and it was a burgeoning town with a strong community. However, by 1870, the good furs became scarce in the rivers and streams of the Pembina hills, and the buffalo had virtually disappeared. By 1871, Walhalla was inhabited only by a priest, the U. S. customs inspector, and some 50 Metis people who had settled here (more or less) permanently. The town revived and was platted in 1877. It was renamed Walhalla by the Icelandic people who were settling in the region. Although most of the Metis inhabitants left the area, some families still remain in the area until today, and each year a festival is held at the Gingras Trading Post State Park. LEROY Originally known as Leroy’s Trading Post, Leroy was established as a Metis community during the 1850s. This post, on the Pembina River, consisted of several households of Metis log cabins scattered in the timber along the river. In 1873, Father LaFlock transferred the Saint Joseph Mission from Walhalla to Leroy to serve the Metis living here, and a post office was established in 1887. Over the decades, the town lost most of its inhabitants to out-migration and old age. The town is now a ghost town, with no census returns during the 2010 census. However, an interesting legend, or ghost story, does persist for Leroy. A road, known as White Lady Lane, goes through the Tetrault Woods between Leroy and Walahalla. Local legend tells of a young girl who became pregnant out of wedlock. Her religious parents forced her to marry the man against her will, and after the wedding, the baby died. The distraught girl hanged herself from a bridge, and her ghost has been seen hanging from the bridge in her wedding dress. The bridge is located down a narrow road off County 9. OLGA This small town, now nearly a ghost town, Olga was originally known as St. Pierre, due to the mission established by Catholic priest, Cyrille Saint Pierre, who was assigned as postmaster in 1882, but it was shortly thereafter renamed Olga in 1883. A small Metis community lived at this location, and it was a favorite camping ground for the Plains Ojibwe and Metis. During the 1800s, and a famous battle between the Ojibwe/Metis and Dakota Sioux—the Battle of O’Brien’s Coulee—took place about a mile from Olga in 1848. References:

WPA Federal Writers Project (1935). North Dakota: A Guide to the Northern Prairie State. Washington: USGPO Barnes-Williams, Mary Ann (1966). Origins of North Dakota Place Names. Bismarck: Tribune Publishing

13 Comments

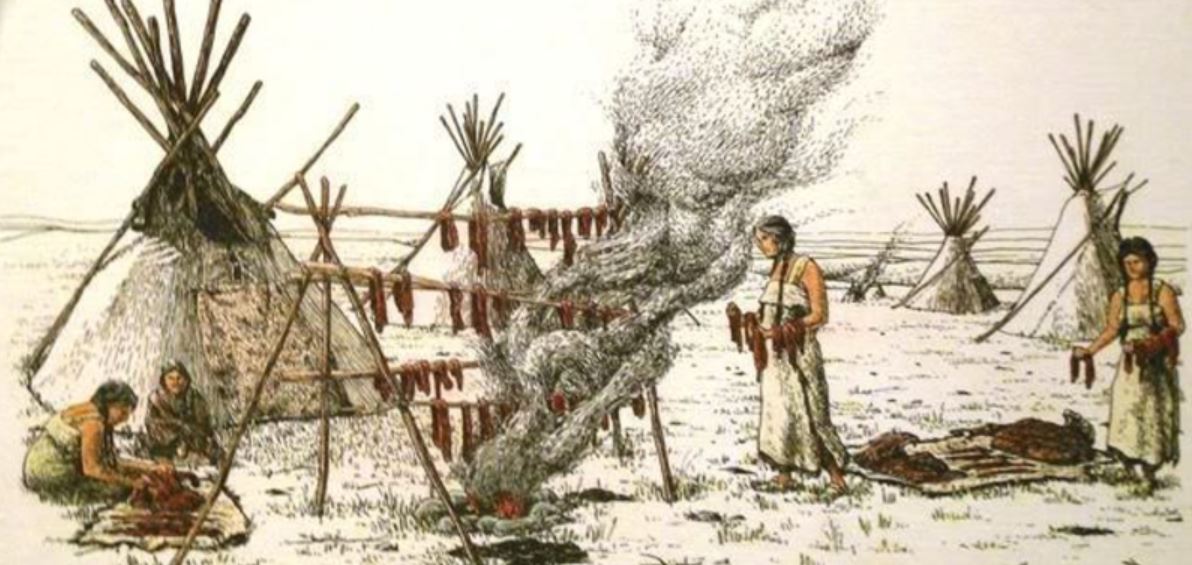

By almost any account you read regarding the subsistence of the indigenous people of the prairies, it is indisputable that Pemmican was the favorite food of the Indians and the Metis. Pemmican can be made from the flesh of any animal, but it was usually made from buffalo meat. The process of making it was to first cut meat into slices, then to dry the meat either by fire or in the sun. Once the meat was dried, it was then pounded into a thick flaky “fluffy” powder. Once rendered down, the meat was put into large bags made from buffalo hides. To this, rendered, melted fat melted fat was poured. The quantity of fat was nearly half the total weight of the finished product, in a portion where for every five pounds of powdered meat, four pounds of fat would be poured. The best pemmican generally saw berries and sugar mixed in for flavor. Once complete, the whole composition formed a solid block that could be cut into portions for later use. Fish was also used to make pemmican. During sturgeon fishing, much of the sturgeon flesh was cured and stored for later use. This was made by drying and pounding sturgeon flesh into a powder, to which sturgeon oil and berries were added. This mixture was then packed into sturgeon skin bags, and used similar to bison pemmican. A person could subsist on buffalo (or fish) Pemmican in good times and lean. Pemmican, with its high fat content, provides a high calorie source of energy that is almost unrivaled. Thus, it was an important food throughout the year, but especially in winter because it stayed “fresh” almost forever and could be stored without worry for years without spoiling. Pemmican could be eaten when other foods were scarce, it could be used to stretch a meal, or it could be eaten on its own just like a block of fatty jerky – a great, portable source of food energy on long hunts or while doing any task where energy was needed. When cooked, Pemmican was easily turned into rubaboo (the most popular method by far) making a delicious stew that could feed an entire camp. Another method was to serve it fried – mixed with a little flour – to create a tasty roux that could be sopped up with bannock bread for a filling meal.

So what does pemmican taste like?' The only way you can describe the taste, is that it tastes 'Like pemmican.' There is nothing else in the world that bears the slightest resemblance. In terms of its quality as a food, it is a ‘super food’. |

AuthorKade M. Ferris, MSc

Archives

June 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed