TRADITIONAL LEADERSHIP

Prior to the establishment of the reservations and the implementation of European ideas of formalized tribal governments, based on the white-colonialist form of government, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa and other Ojibwe bands operated on a traditional system of government that worked well for centuries.

The head chief was often a hereditary position, such as with the Little Shell Chiefs, but others could be elevated to that level through great achievements, or through the will of the people. The position of head chief, depended much on their wisdom, bravery and hospitality as leaders and their influence could serve to attract people to follow and join the band – thereby creating a very strong collective under a great leader.

It was the job of the chief to make sure that people had enough. The chief was supposed to always set a good example in hunting and trapping and in family life…he'd go around and make sure that people were able to take care of themselves and their families. If they weren't, he'd talk to them, find out why, and try to come up with a solution to help them improve. Whenever somebody was sick or couldn't provide their family with food, the chief would appoint a counselor, or a group of men, to go around and collect tea, snuff, sugar, lard, flour, and other goods to help out the family. Everybody had to make a contribution.

The duties of a chief included the presiding at councils of his band, making important decisions that affected the general welfare of the band, and the settlement of small disputes. He represented the band at the signing of treaties, the payment of annuities, and any large gathering of the tribe. However, the chief did not act alone.

Associated with the chief were two “head men” who acted as his protectors and trusted advisors. They were selected from among the warriors and each head man had something to do. One was sort of like a policeman; he had to keep the peace and look after complaints, while the other provided wise advice and was active within the community. Other head men, serving as assistants, would act in various capacities as messengers, spokesmen, or arbiters of justice. One head man assistant was the chief's administrator, who among other things distributed various goods to persons who were in need and who heard complaints from those who needed help. There was even an honorary chief, appointed a kind of spokesman, who would work with the youth and children of the band and who would teach them about the Indian way of life. He was an old man with great wisdom and understanding. In addition to these, there was also a group of older people who were like elder advisers to the chief. They offered their words of wisdom and provided advice to the chief to help him make decisions.

Unlike today, when Tribal councils often work behind closed doors, the traditional work of the chief and council never decided important things alone, or in secrecy. They would call a meeting; calling for everybody to come to the community hall where decisions would be made in the open, and where people would have a chance to speak up if needed.

The head chief was often a hereditary position, such as with the Little Shell Chiefs, but others could be elevated to that level through great achievements, or through the will of the people. The position of head chief, depended much on their wisdom, bravery and hospitality as leaders and their influence could serve to attract people to follow and join the band – thereby creating a very strong collective under a great leader.

It was the job of the chief to make sure that people had enough. The chief was supposed to always set a good example in hunting and trapping and in family life…he'd go around and make sure that people were able to take care of themselves and their families. If they weren't, he'd talk to them, find out why, and try to come up with a solution to help them improve. Whenever somebody was sick or couldn't provide their family with food, the chief would appoint a counselor, or a group of men, to go around and collect tea, snuff, sugar, lard, flour, and other goods to help out the family. Everybody had to make a contribution.

The duties of a chief included the presiding at councils of his band, making important decisions that affected the general welfare of the band, and the settlement of small disputes. He represented the band at the signing of treaties, the payment of annuities, and any large gathering of the tribe. However, the chief did not act alone.

Associated with the chief were two “head men” who acted as his protectors and trusted advisors. They were selected from among the warriors and each head man had something to do. One was sort of like a policeman; he had to keep the peace and look after complaints, while the other provided wise advice and was active within the community. Other head men, serving as assistants, would act in various capacities as messengers, spokesmen, or arbiters of justice. One head man assistant was the chief's administrator, who among other things distributed various goods to persons who were in need and who heard complaints from those who needed help. There was even an honorary chief, appointed a kind of spokesman, who would work with the youth and children of the band and who would teach them about the Indian way of life. He was an old man with great wisdom and understanding. In addition to these, there was also a group of older people who were like elder advisers to the chief. They offered their words of wisdom and provided advice to the chief to help him make decisions.

Unlike today, when Tribal councils often work behind closed doors, the traditional work of the chief and council never decided important things alone, or in secrecy. They would call a meeting; calling for everybody to come to the community hall where decisions would be made in the open, and where people would have a chance to speak up if needed.

The Little Shell DynastyHereditary chiefs, as the name implies, are those leaders who earned the title of Ogema (Chief) and who in turn passed their leadership down to a worthy heir who inherited the title and responsibilities according to the history and cultural values of the Turtle Mountain Anishinaabe community. Their governing principles were anchored in the cultural traditions of the people.

Hereditary chiefs carried the responsibility of ensuring that the traditions, protocols, songs, and dances of the community - which have been passed down for hundreds of generations - were respected and kept alive. They were the caretakers of the people and the culture in times of peace and times of war. The only true hereditary chiefs of the Pembina and Turtle Mountain Band are the "Little Shell" chiefs who led the Pembina Band from about 1770 until 1903. |

AISANCE: LITTLE SHELL I

TERM OF LEADERSHIP: 1770-1813

The name “Little Shell” was carried by three head Chiefs of the Pembina/Turtle Mountain Band. The title was assumed by each, in turn, as he succeeded to the chieftainship. Each had his individual name by which he was known to his friends and relatives. According to Turtle Mountain Chippewa history, the title Little Shell was handed down from father to son.

Soon after the Pembina Band’s emergence as a separate band of Chippewa, the first Chief Little Shell was recognized as its chief. The residence of the first Little Shell was near Devil's Lake on what is now known as Graham’s Island. Little Shell also oversaw other villages in the Turtle Mountains, several camps west of present-day Rugby, a fortified encampment near a small lake south of Willow City, and another village near Buffalo Lodge Lake.

He was killed by a party of Dakota Sioux sometime around 1813 while encamped at his home at Graham’s Island.

The name “Little Shell” was carried by three head Chiefs of the Pembina/Turtle Mountain Band. The title was assumed by each, in turn, as he succeeded to the chieftainship. Each had his individual name by which he was known to his friends and relatives. According to Turtle Mountain Chippewa history, the title Little Shell was handed down from father to son.

Soon after the Pembina Band’s emergence as a separate band of Chippewa, the first Chief Little Shell was recognized as its chief. The residence of the first Little Shell was near Devil's Lake on what is now known as Graham’s Island. Little Shell also oversaw other villages in the Turtle Mountains, several camps west of present-day Rugby, a fortified encampment near a small lake south of Willow City, and another village near Buffalo Lodge Lake.

He was killed by a party of Dakota Sioux sometime around 1813 while encamped at his home at Graham’s Island.

MAKADESHIB: BLACK DUCK

TERM OF LEADERSHIP: 1813-1815

Following the death of the first Little Shell, Makadishib (Black Duck) – the father-in-law of Little Shell – assumed leadership of the band as 'regent'. Black Duck maintained a camp at the Turtle Mountains, oversaw the villages near Pembina and Walhalla, and lived in his main village at Stump Lake. His Stump Lake village was at the location of a former Hidatsa Village – the last Hidatsa Village east of the Missouri River – which Black Duck and his warriors had taken by force around 1800.

Black Duck served as the leader of the Pembina not as a hereditary chief, but only until the son of the first Little Shell came of age and could assume his role as leader in 1815.

Black Duck and his warriors were killed by a party of Dakota Sioux near the present-day community of Wild Rice, North Dakota, in about 1824.

Following the death of the first Little Shell, Makadishib (Black Duck) – the father-in-law of Little Shell – assumed leadership of the band as 'regent'. Black Duck maintained a camp at the Turtle Mountains, oversaw the villages near Pembina and Walhalla, and lived in his main village at Stump Lake. His Stump Lake village was at the location of a former Hidatsa Village – the last Hidatsa Village east of the Missouri River – which Black Duck and his warriors had taken by force around 1800.

Black Duck served as the leader of the Pembina not as a hereditary chief, but only until the son of the first Little Shell came of age and could assume his role as leader in 1815.

Black Duck and his warriors were killed by a party of Dakota Sioux near the present-day community of Wild Rice, North Dakota, in about 1824.

WEESH-E-DAMO: Little Shell II

TERM OF LEADERSHIP: 1815-1872

Recognized by the Pembina people as their leader due to his birthright, Weesh-e-damo assumed his role as Chief Little Shell II in 1815. He was instrumental in leading the Pembina to claim vast swaths of what is now eastern and western North Dakota. His territory expanded west into southern Canada as far as Wood Mountain.

Weesh-e-damo was formally recognized by the United States Government as Chief of the Pembina Band during negotiations of the failed, unratified 1851 Treaty at Pembina. By 1862, he was referred to most frequently as chief of the Turtle Mountain Band, but was also acknowledged to the supreme leader of the Pembina Chippewa despite attempts by the US government to undermine his leadership by appointing hand-picked "chiefs" who were more friendly to the colonial powers. Despite this, Weesh-e-damo's leadership was unchallenged even by Chief Red Bear who was appointed by the US prior to treaty negotiations in 1863.

While Weesh-e-damo signed the 1863 Treaty at the Old Crossing, he refused to sign a subsequent revision offered by the US government (in 1864) that he felt undermined some of the treaty stipulations.

Recognized by the Pembina people as their leader due to his birthright, Weesh-e-damo assumed his role as Chief Little Shell II in 1815. He was instrumental in leading the Pembina to claim vast swaths of what is now eastern and western North Dakota. His territory expanded west into southern Canada as far as Wood Mountain.

Weesh-e-damo was formally recognized by the United States Government as Chief of the Pembina Band during negotiations of the failed, unratified 1851 Treaty at Pembina. By 1862, he was referred to most frequently as chief of the Turtle Mountain Band, but was also acknowledged to the supreme leader of the Pembina Chippewa despite attempts by the US government to undermine his leadership by appointing hand-picked "chiefs" who were more friendly to the colonial powers. Despite this, Weesh-e-damo's leadership was unchallenged even by Chief Red Bear who was appointed by the US prior to treaty negotiations in 1863.

While Weesh-e-damo signed the 1863 Treaty at the Old Crossing, he refused to sign a subsequent revision offered by the US government (in 1864) that he felt undermined some of the treaty stipulations.

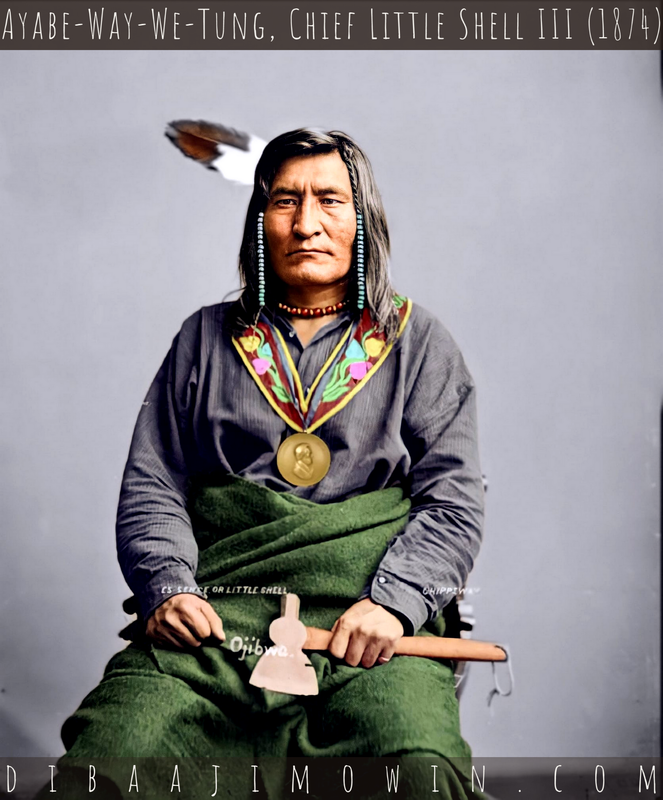

AYABE-WAY-WE-TUNG: Little Shell III

TERM OF LEADERSHIP: 1872-1903

After the passing of his father in 1872, Ayabe-way-we-tung became the third Little Shell Chief.

His first order of business as chief was to negotiate with Washington, hoping to secure an amenable treaty for his people for their lands in North Dakota, and for the establishment of a reservation that would serve them as a permanent homeland against the encroachment of white settlers. During his delegation of 1876, Little Shell and the other leaders of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa made a petition to the US Government asking for a settlement of their issues. They made several key points and concessions, and asked for considerations for their request to cede over 9-million acres of land in North Dakota. Among their main points were to define their territory formally with the government, to lodge a complaint about the establishment of the Sioux reservation at Devils Lake, and to ask for the establishment of a formal reservation of 50 by 60 miles in the area surrounding the Turtle Mountains. Unfortunately, the government refused to act upon their petition and soon thereafter a smaller reservation was established by Executive order in 1882. This reservation was further diminished in 1884 to the present-day size of 6 by 12 miles. The reduction of the reservation remained a bone of contention for Little Shell throughout all future negotiations with the government.

In 1892, negotiations between the government and the tribe were arbitrarily commenced in order to settle the title to 10-million acres of land yet unceded by Little Shell and the Turtle Mountain Band. The negotiating committee was headed by P. J. McCumber, and became known as the McCumber Commission. Even though Little Shell was the hereditary chief of the Band, the McCumber Committee refused to negotiate with him and his council – forcing Little Shell to walk out of the negotiations in protest. Taking advantage of this, McCumber instead undercut Little Shell by dealing with a “Committee of 32” which had been elected the previous year to deal with some internal problems within the tribe. The result of this negotiation was the so-called “Ten Cent Treaty” by which the Turtle Mountain Band, under the Committee of 32, agreed to cede their claims to their nearly 10-million acres of land for one-million dollars. This “treaty” was quickly contested by Little Shell and his council, who spent the next twelve years in a legal battle with the US Government. As a result, the Ten Cent Treaty was never ratified by Congress.

Little Shell III passed away in 1903 and Congress quickly ratified an amended McCumber Agreement (the Davis Agreement) in 1904.

After the passing of his father in 1872, Ayabe-way-we-tung became the third Little Shell Chief.

His first order of business as chief was to negotiate with Washington, hoping to secure an amenable treaty for his people for their lands in North Dakota, and for the establishment of a reservation that would serve them as a permanent homeland against the encroachment of white settlers. During his delegation of 1876, Little Shell and the other leaders of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa made a petition to the US Government asking for a settlement of their issues. They made several key points and concessions, and asked for considerations for their request to cede over 9-million acres of land in North Dakota. Among their main points were to define their territory formally with the government, to lodge a complaint about the establishment of the Sioux reservation at Devils Lake, and to ask for the establishment of a formal reservation of 50 by 60 miles in the area surrounding the Turtle Mountains. Unfortunately, the government refused to act upon their petition and soon thereafter a smaller reservation was established by Executive order in 1882. This reservation was further diminished in 1884 to the present-day size of 6 by 12 miles. The reduction of the reservation remained a bone of contention for Little Shell throughout all future negotiations with the government.

In 1892, negotiations between the government and the tribe were arbitrarily commenced in order to settle the title to 10-million acres of land yet unceded by Little Shell and the Turtle Mountain Band. The negotiating committee was headed by P. J. McCumber, and became known as the McCumber Commission. Even though Little Shell was the hereditary chief of the Band, the McCumber Committee refused to negotiate with him and his council – forcing Little Shell to walk out of the negotiations in protest. Taking advantage of this, McCumber instead undercut Little Shell by dealing with a “Committee of 32” which had been elected the previous year to deal with some internal problems within the tribe. The result of this negotiation was the so-called “Ten Cent Treaty” by which the Turtle Mountain Band, under the Committee of 32, agreed to cede their claims to their nearly 10-million acres of land for one-million dollars. This “treaty” was quickly contested by Little Shell and his council, who spent the next twelve years in a legal battle with the US Government. As a result, the Ten Cent Treaty was never ratified by Congress.

Little Shell III passed away in 1903 and Congress quickly ratified an amended McCumber Agreement (the Davis Agreement) in 1904.

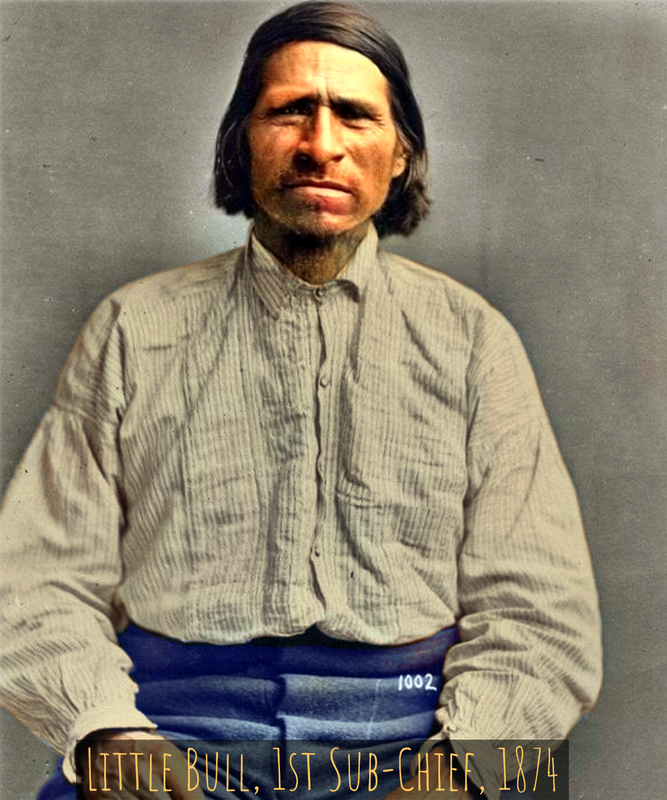

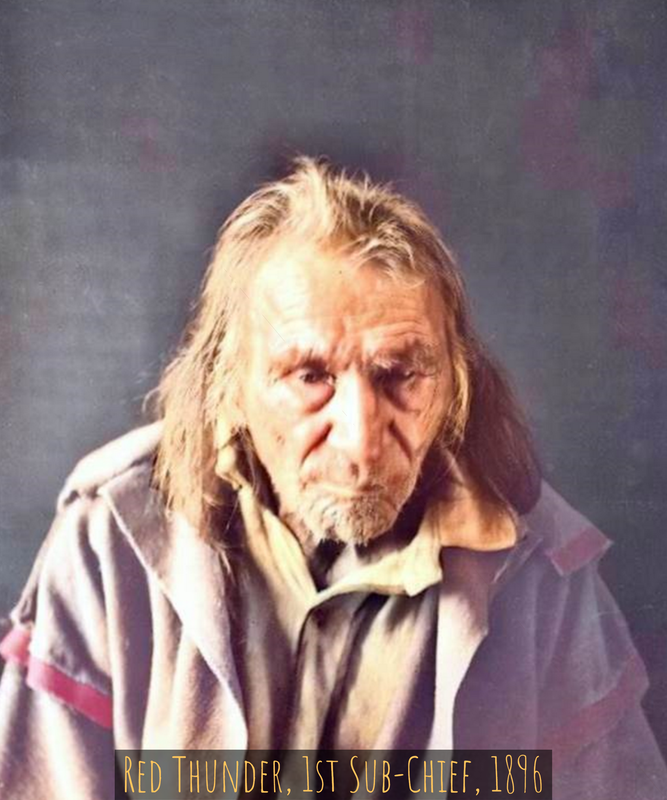

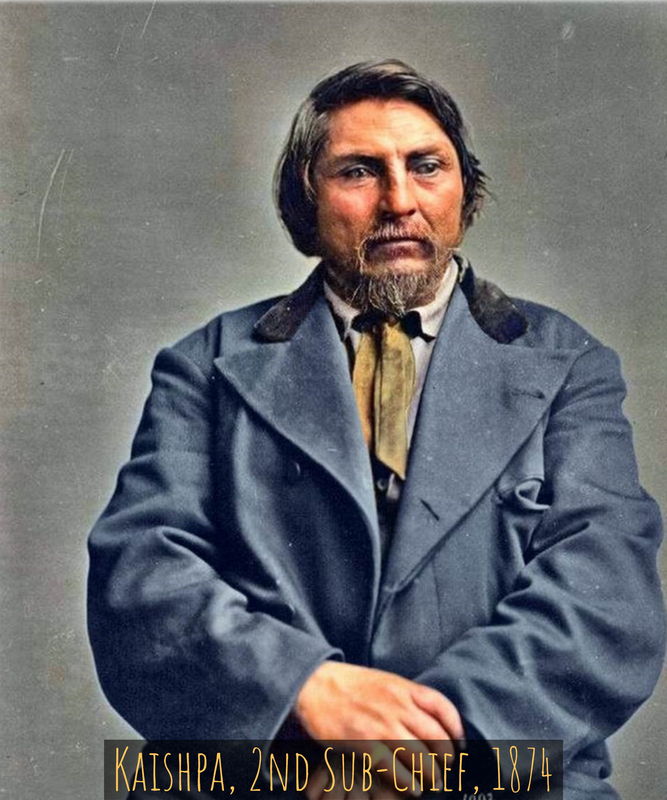

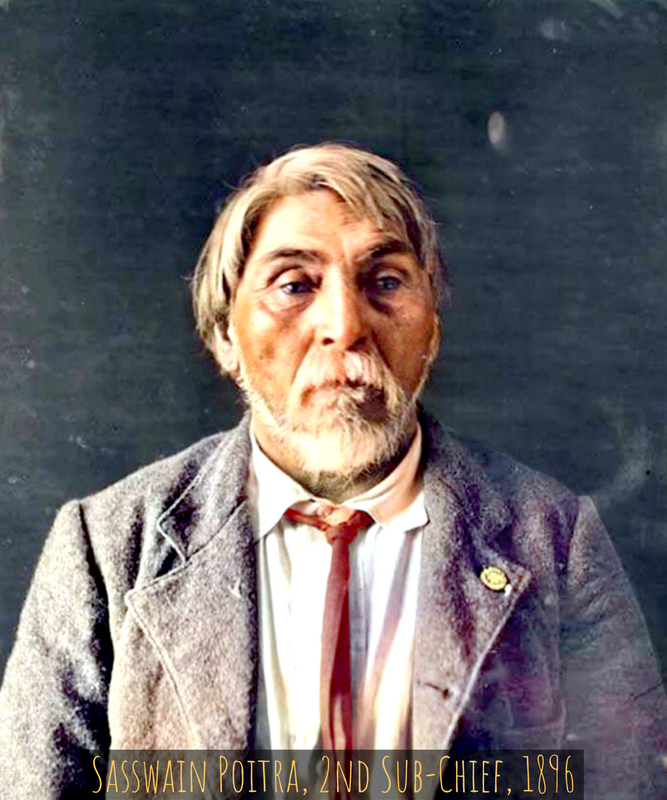

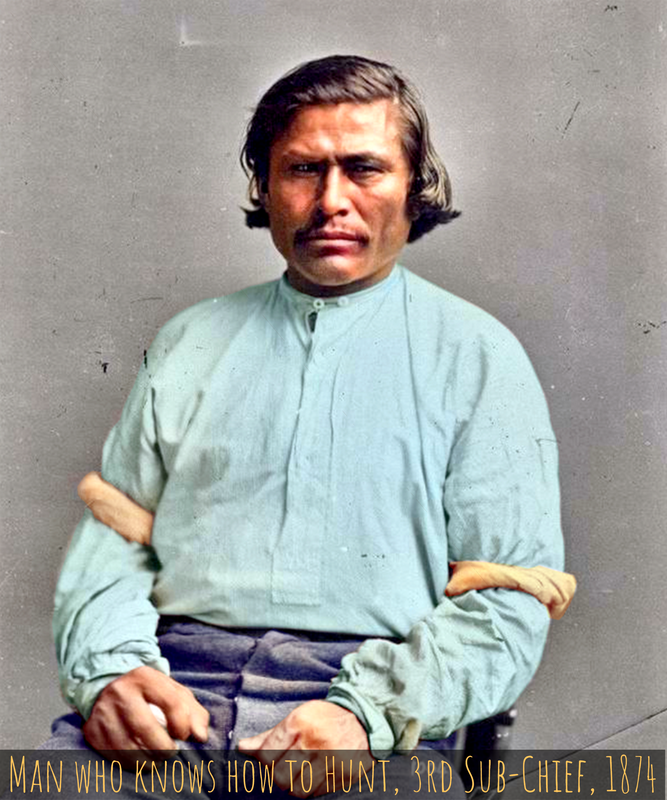

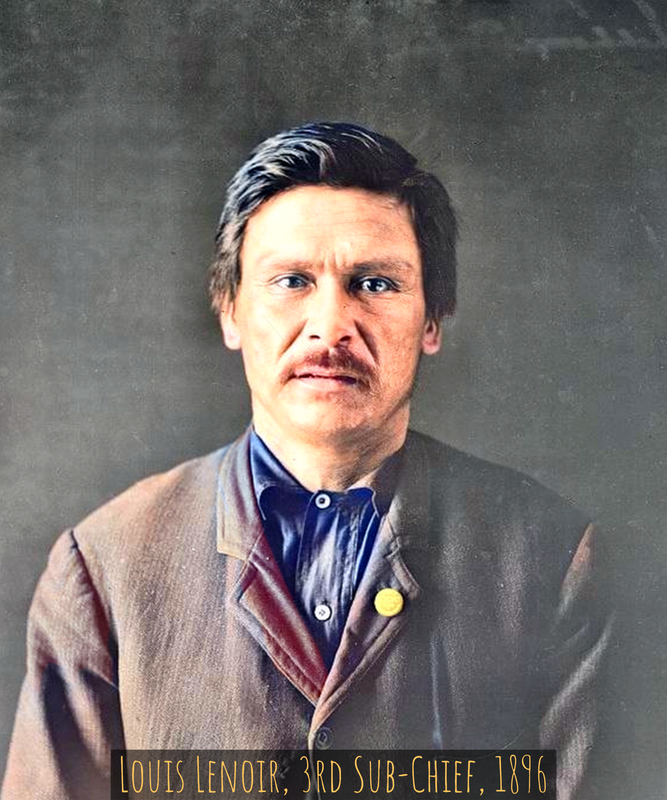

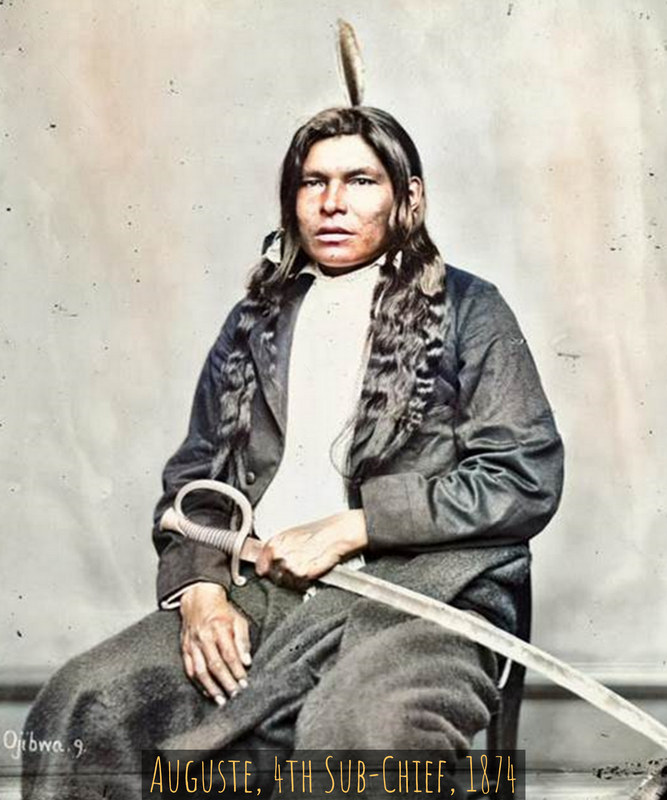

Sub-Chiefs of Little Shell

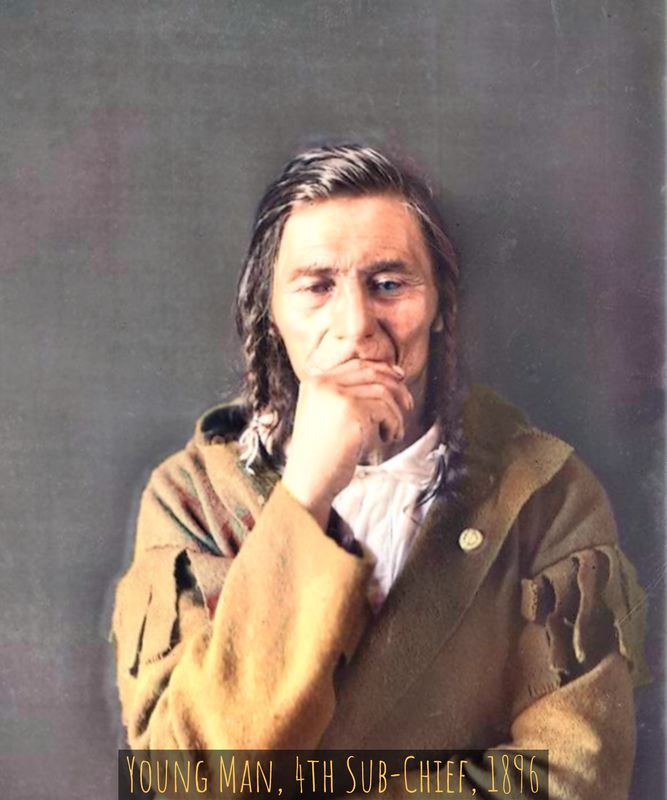

Hereditary chiefs were usually served by four worthy men who acted as sub-chief, or headmen. In this capacity, these men would dispense justice, care for the poor and sick members of the tribe, and carry out the wishes of the chief. Their roles were not hereditary and they were chosen at the will of the chief.

The following individuals were sub-chiefs (headmen) under Little Shell III:

The following individuals were sub-chiefs (headmen) under Little Shell III:

Government Appointed Chiefs

As opposed to hereditary chiefs, who served at the will of the people and under traditions, government appointed chiefs were leaders who were granted the title of Chief by the United States Government for the purposes of negotiating treaties or leading in the absence of the hereditary chiefs. Their title and chiefdoms were not inherited by their sons, but they are remembered as chiefs, nonetheless, due to the leadership they often provided.

'Misko-Makwa' Red Bear

Served as a chief of a competing group of Pembina before and during the 1863 treaty. After signing the 1864 amendment, his influence waned and his group of followers was absorbed under Little Shell’s leadership.

‘Way-shaw-wash-ko-quen-abay’ Green Setting Feather (also called Sakikwanel)

Was appointed “chief” of the Indians camped at Pembina by Major Samuel Wood while Little Shell II was away in Canada at Wood Mountain, Sasktachewan.

‘Majekkwadjiwau’ End of the Current

Appointed as 1st sub-chief by Maj. Wood

‘Kakakanawakkagan’ Long Legs

Appointed as 2nd sub-chief by Maj. Wood

'Misko-Makwa' Red Bear

Served as a chief of a competing group of Pembina before and during the 1863 treaty. After signing the 1864 amendment, his influence waned and his group of followers was absorbed under Little Shell’s leadership.

‘Way-shaw-wash-ko-quen-abay’ Green Setting Feather (also called Sakikwanel)

Was appointed “chief” of the Indians camped at Pembina by Major Samuel Wood while Little Shell II was away in Canada at Wood Mountain, Sasktachewan.

‘Majekkwadjiwau’ End of the Current

Appointed as 1st sub-chief by Maj. Wood

‘Kakakanawakkagan’ Long Legs

Appointed as 2nd sub-chief by Maj. Wood

The Half-Breed Chiefs of 1850

In 1850, Major Samuel Wood visited Pembina and attempted to organize the Metis (half-breeds) under a 9-person council in an attempt to separate the mixed-blood Chippewa from the full-bloods so as to negotiate for a surrender of rights from the mixed-bloods. These men were deemed to be leaders as most were prominent hunters and warriors who commanded respect and were followed by large, extended family groups.

The nine men chosen to lead the Metis as "chiefs" were as follows:

Headman: J.B. Wilkie (b. 1803 – d. 1886)

Councilor: J.B. Dumont (b. 1799 – d. 1884)

Councilor: Baptiste Vallee (b. 1810 - d. ???)

Councilor: Edward Harmon (b. ca. 1805 - d. ???)

Councilor: Joseph Laverdure (b. 1814 – d. 1888)

Councilor: Joseph Nolin (b. 1804 – d. 1872)

Councilor: Antoine “Labelle” Azure (b. 1794 – d. ???)

Councilor: Robert “Bonhomme” Montour (b. 1787 - d. 1857)

Councilor: Baptiste Lafournaise (b. 1815 – d. ???)

The nine men chosen to lead the Metis as "chiefs" were as follows:

Headman: J.B. Wilkie (b. 1803 – d. 1886)

Councilor: J.B. Dumont (b. 1799 – d. 1884)

Councilor: Baptiste Vallee (b. 1810 - d. ???)

Councilor: Edward Harmon (b. ca. 1805 - d. ???)

Councilor: Joseph Laverdure (b. 1814 – d. 1888)

Councilor: Joseph Nolin (b. 1804 – d. 1872)

Councilor: Antoine “Labelle” Azure (b. 1794 – d. ???)

Councilor: Robert “Bonhomme” Montour (b. 1787 - d. 1857)

Councilor: Baptiste Lafournaise (b. 1815 – d. ???)