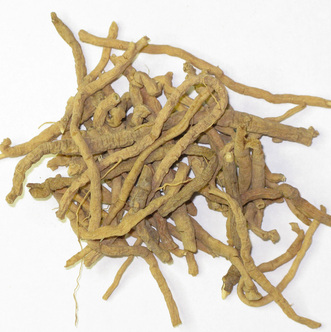

Seneca Snakeroot Below are some medicines used by the Turtle Mountain Chippewa to cure common ailments. Please do not try these remedies at home. Always consult a medicine man before using these remedies... _______________________________________________ White Pine. The needles of the white pine could be crushed and applied to relieve headache. The vapors of boiled white pine could be inhaled to cure backache. The smoke (fumes) of the needles heated upon a stone or a hot iron pan could also be inhaled to cure headache. Balsam Fir. The bark was scraped from the trunk and a tea made to induce sweating, or it could be applied externally to sores and cuts. White Cedar. The leaves could be crushed and the vapors (smudge) could be used to drive out bad spirits possessing an individual. Red Cedar. Bruised leaves and berries are used internally to remove headache. White Oak. The bark of the root and the inner bark scraped from the trunk is boiled into a tea used to treat diarrhea. Sugar Maple. In addition to its use in making maple sugar, the inner bark could be made into a tea used to treat diarrhea. Black Sugar Maple. Like sugar maple, its inner bark could be made into a tea used to treat diarrhea. Cottonwood. The cottonwood down could be applied to open sores as an absorbent. Sunflower. The crushed root could be applied to bruises and contusions to speed the healing process. Seneca Snakeroot. A tea could be made from the roots to treat colds and cough, and the leaves could also be brewed into a tea for sore throat. Wild Raspberry. A tea made from the crushed roots could be taken to relieve pains in the stomach. Wild Black Cherry. The inner bark can be applied to external sores, either by first boiling, bruising, or chewing it, and a tea made from the inner bark is sometimes given to relieve pains and soreness of the chest. Wild Red Cherry. A tea made from the crushed root can be given for pains and other stomach disorders. Common Cattail. The roots could be crushed by pounding or chewing, and applied as a poultice to sores. Black Ash. The inner bark could be soaked in warm water, and the liquid applied to sore eyes. Bitter Root. A tea made from the crushed root could be taken as a purgative. Currant. The inner bark of the root could be boiled and the tea, when cold, applied to sore eyes. Dwarf Wild Rose. The roots of young plants were steeped in hot water and the liquid applied to sore eyes.

22 Comments

The man on the phone said simply, “We want you to help our tribe start a weekly newspaper.”

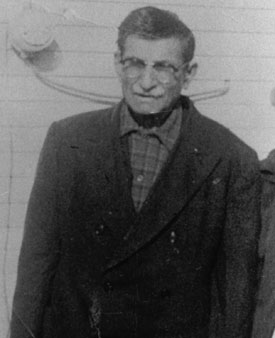

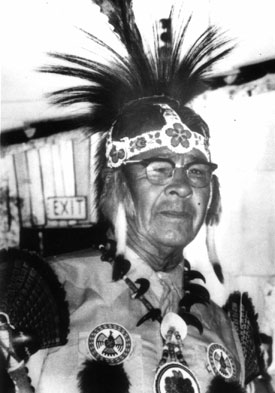

The man on the line was Richard J. “Jiggers” LaFramboise, then chairman of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa and the year was 1992. I flew up to the Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota not too long after that call and met with Jiggers and his staff. We discussed the ways and means of starting a newspaper, set a price and got down to the business of starting a newspaper in Belcourt, the main community on the reservation. Turtle Mountain is in the Northeastern part of North Dakota right on the Canadian border. In fact you can cross into Canada from Turtle Mountain. Back in the old days when the French Canadians and the Metis played an important role on many of the Northern Indian reservations, one of their favorite things was a fiddle and a dance known as the jig. In his youth Richard LaFramboise was quite handy at doing the jig, and hence the nickname “Jiggers.” Well, Jiggers had his mind set on economic development. He secured a contract with the federal government using a closed military plant to construct trailers. The contract brought 200 new jobs to Turtle Mountain where the unemployment rate hovered at 50 percent. With money left over from the block grant, he built the Heritage Center. He also built the community bowling alley and added new businesses to the tribal mall. Jiggers brought the tribe’s gross income from $23 million in 1992 to $200 million in 1994. The tribe’s schools, community college and the reservations roads and highways all saw considerable improvements during Jiggers’ terms in office. But in 1992 he wanted to improve communications on the reservation. He already had a radio station, KEYA-FM, but now Jiggers wanted a newspaper because he was a firm believer in the power of the press. I told him that he had to choose a strong editor because knowing tribal politics as both of us did, the time would come when politicians would find a reason to interfere with the freedom of the press. Jiggers chose Robin Poitra Powell as his editor and then he picked Shirley Belgarde and Logan Davis as staff members. The training took several weeks. Powell, Belgarde and Davis flew down to Rapid City and started working daily at Indian Country Today, the paper I owned back then. Powell dug into the editorial side of the paper working diligently with our writers, proof readers and editors. Davis worked with my then sales manager Lynette Two Bulls and the advertising sales staff, and Belgarde worked every day with Christy Tibbetts and the bookkeeping and office crew. We figured we would then have an editor to put out the newspaper every week, a sales manager to bring advertising dollars to the paper, and an office manager to handle all of the accounts payable and receivable. That would give the paper a strong nucleus. Our next step was to find a location at Turtle Mountain and to purchase the equipment necessary for a start-up. I talked Rick Musser, a professor of journalism at the University of Kansas, to join our efforts. Musser and I, plus several of our staff members, drove up to Turtle Mountain to complete this next step. The Tribe offered one of the newly constructed homes to house the new venture and we got on the phone to order desks, file cabinets, chairs and, of course, computers. Musser worked with the team that had just returned from Rapid City in organizing the office and staff and to prepare for the first issue of the paper that would be named The Turtle Mountain Times. After all of the phones and other electronic equipment was in place, the Turtle Mountain Times hit the streets in June of 1993. Next year the newspaper will be celebrating its 20th anniversary and of all of the employees who trained in those beginning days, Shirley Belgarde is still working at the paper. Others have moved on, but the newspaper is still hitting the streets every Wednesday. Belgarde said, “We still have to survive every new administration change and each time this happens we are often threatened with having our funding reduced or cut altogether, but that’s tribal politics and we are about to face another administration change.” I know how that goes because after “Jiggers” left office the new administration decided that the debt he incurred in starting the Turtle Mountain Times was no longer relevant, and my company was left holding the bag. It was a lesson learned and life goes on as does the newspaper that we got off of the ground. I am still very proud of the Turtle Mountain Times because it survived for nearly 20 years in the face of economic downturns and the ever-changing tribal administrations. “Jiggers” had a dream and that dream became a reality. To Shirley Belgarde and those early newspaper pioneers, I say congratulations, good luck, and keep the presses rolling. Tim Giago, an Oglala Lakota, is President of Unity South Dakota. He was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard with the Class of 1990. His weekly column won the H. L. Mencken Award in 1985. He was the founder of The Lakota Times, Indian Country Today, Lakota Journal and Native Sun News. He can be reached at [email protected] The Chairmen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa since the establishment of the Tribe under the constitution of 1932:

|

Author

Content is provided by Kade M. Ferris M.S. Kade has a B.A. in anthropology and history from University of North Dakota, and a M.S. degree in anthropology from North Dakota State University. Kade serves as the Historical Society board Vice President and is a professional historian and anthropologist with over 18 years of experience. He serves as the THPO and Director of Natural Resources for the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, and is the Vice President of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa Historical Society Board. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed