|

Noted fur trader, Alexander Ross, described a Metis and Ojibwe hunting expedition that took place in 1840. According to Ross, two expeditions were undertaken that year by a group that include about 1,630 men, women, and children. The hunters started their hunt leaving from Red River Colony where they made a stop at Fort Garry to purchase supplies before traveling south to Pembina. In his description, Ross gives detailed information about the highly organized political organization of the hunting party and the rules followed by the hunters while on the march.

According to Ross, “The first step was to hold a council for the nomination of chiefs or officers. Then captains were named, the senior [leader] on this occasion being Jean Baptiste Wilkie, an English half-breed, brought up among the French. Besides being captain…[Wilkie] was styled the great war chief or head of the camp; and on all public occasions he occupied the place of president. Each captain had ten soldiers under his orders; in much the same way that policemen are subject to a magistrate. Ten guides were likewise appointed. Their duties were to guide the camp, each in his turn -- that is day about -- during the expedition. "The hoisting of the flag every morning is the signal for raising camp. Half an hour is the full time allowed to prepare for the march; but if anyone is sick, or their animals have strayed, notice is sent to the guide, who halts until all is made right. From the time the flag is hoisted, however, till the hour for camping arrives, it is never taken down. The flag taken down is the signal for encamping. While it is up, the guide is chief of the expedition and the Captains are subject to him, and the soldiers of the day are his messengers: he commands all. The moment the flag is lowered, his functions cease, and the captains' and soldiers' duties commence. They point out the order of the camp, and every cart, as it arrives, moves to its appointed place." Ross further stated that the captains and other chief men laid down rules to be observed by the hunters. Most of these rules concern restrictions on hunting without general orders being given, and the punishment for infractions of these rules. The hunt of 1840 left Pembina on the 21st of June. While on the march, many of the hunters and their families experienced severe hunger. On the ninth day the expedition reached the Sheyenne River without having seen any buffalo. But on the nineteenth day, along the Missouri River, the hunters finally encountered buffalo on July 4th. About 400 huntsmen, all mounted took up their position in a line at one end of the camp while Captain Wilkie surveyed the buffalo, examined the ground, and issued his orders. At the end of the day’s hunt, 1,375 buffalo had been harvested. -------------------- SOURCE: Red Lake & Pembina Chippewa by Voegelin and Hickerson, ICC Docket 18A

2 Comments

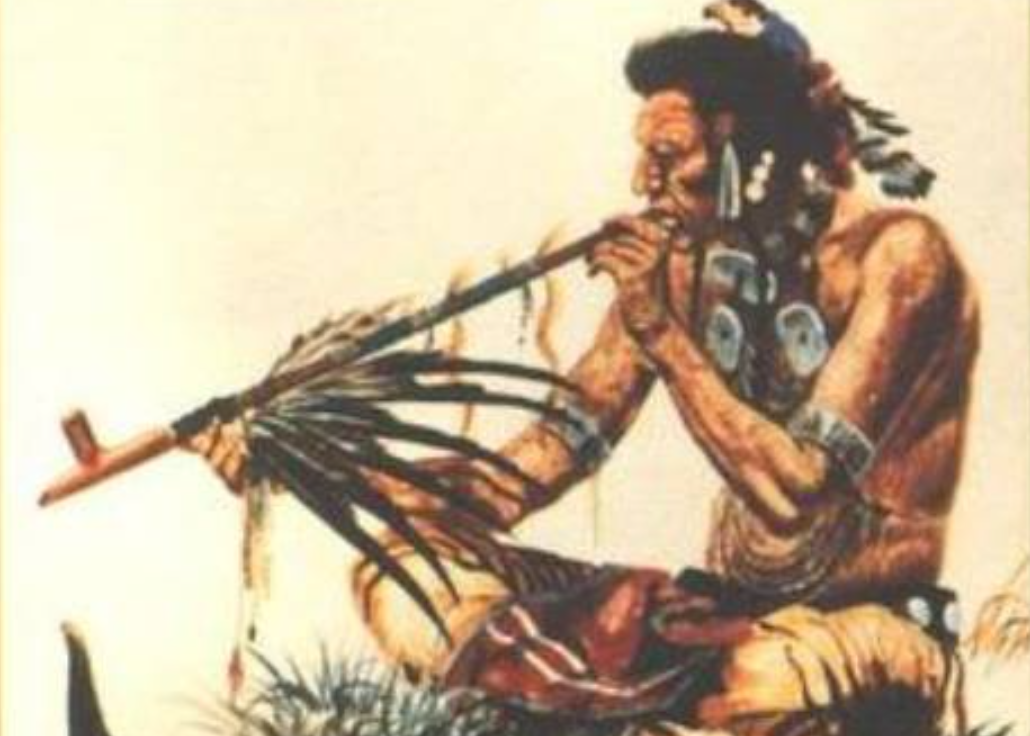

Makadeshib (Black Duck) was a brave warrior and early chief of the Pembina Band of Ojibwe. He maintained his home camps and hunted at Stump Lake and near Fargo, North Dakota during the early years of the 1800s. In about 1824, Makadeshib decided to go to war against the Dakota. He sent around tobacco and raised a war party that left Pembina, marching towards Lake Traverse (Sisseton, South Dakota). The march took thirteen days. The war party searched the area around Big Stone Lake and Lake Traverse, but did not find their enemies. The war party then proceeded west towards Ogema-Wadju (Chief Mountain), a large hill where the Dakota were known to camp. Not finding a village there, the war party soon became disenchanted. Chief Peguis, who was part of the war party, took his men and returned home, but the remaining men who stayed with Makadeshib kept searching until they came upon a village of about 300 Dakota. That night they attacked, and the fight was a resounding victory for Makadeshib and his troops. However, a few Dakota were able to escape and they made their way to a nearby camp where they roused more warriors who quickly came to press the fight against the Ojibwe. Out of bullets and tired from the fight, Makadeshib and his men retreated as quickly as they could, but they saw that they would soon be overtaken. Knowing that they would all be slaughtered in the upcoming fight, it was decided that most of the men would keep running, while a small party remained with Makadeshib to fight and secure their escape. Makadeshib and his stalwart companions calmly took off their clothes down to their breechcloths, folded them into bundles, then they took out their pipes and smoked and prayed to the manitou for pity. Almost 300 Dakota warriors came upon them and the fighting was hand-to-hand. During the short battle, 13 warriors fell, including Makadeshib. One man escaped across the river and was able to sneak away to report the fate of his companions and the brave Makadeshib. This final battle took place near modern-day Wild Rice, North Dakota, a small town south of Fargo.

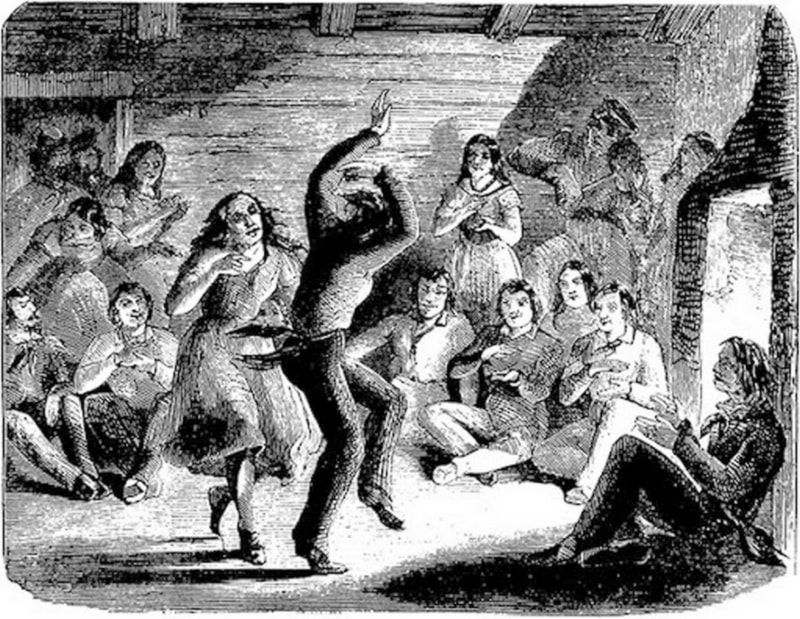

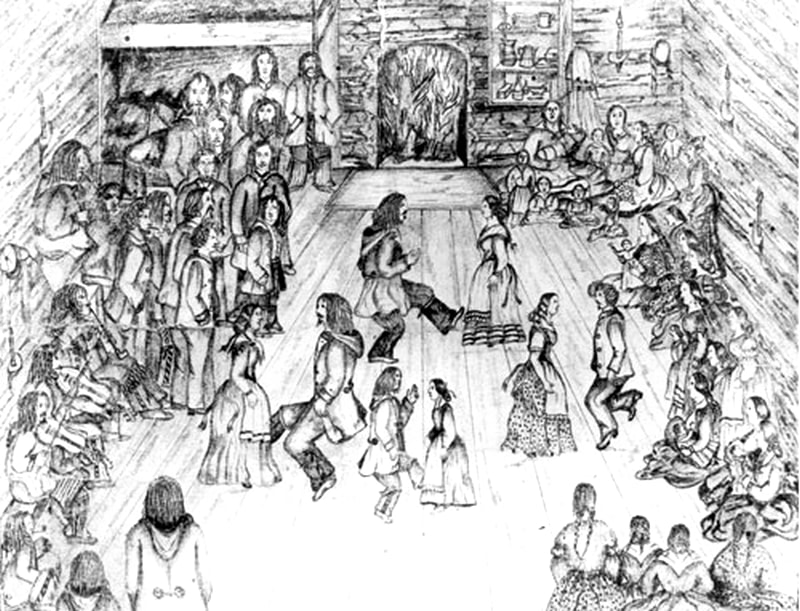

During the middle-1800s, a priest named Father Genin - who ministered to the Ojibwe and Dakota - was told about the bravery of Makadeshib and his men. Father Genin went to the location where they fell and ordered the erection of a large, white cross at the spot where they had died. Years later, as white men finally came to North Dakota after the land was opened up following the 1863 Old Crossing Treaty, many settlers were surprised to see the white cross as they crossed the Red River. Most were unaware that this location was where a mighty warrior and his brave men lost their lives. Makadeshib is relatively unknown today, but many of his descendants can be found at Cypress Hills and Cowessess Reserve in Canada, and at Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota. ---------- SOURCES: Henry Rowe Schoolcraft. Indian Tribes of the United States. (1884) O.G. Libby. Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, Volume 1. (1906) In traditional Indigenous communities, music and dance are some of the most important ways to preserve and promote culture and to bring people together. While music and dance that are ceremonial in nature preserve our spirituality, secular songs and dances that appeal to our nature of fun, family, and friendship are the ones that are often the most celebrated and which appeal to the broadest segments of our people. Contemporary Pow-wows, for example, are important cultural-revivals that present the most colorful aspects of our expression as Indigenous people. They evoke emotional and psychological overtones that go far beyond the pursuit of entertainment and enjoyment, yet at the end of the day they are at the heart of what makes our communities thrive, generation after generation. The same can be said of the traditional jig dancing of the Metis people.  From the earliest times of the Metis ethnogensis, the Metis took part in the traditional Indian dances of their mothers' peoples. But as missionaries began to exert more control over the Metis, participation in such dancing was greatly discouraged as "savage" and improper as the missionaries thought such dancing was tied to pagan ceremonies. However, the social dances of European and French-Canadian origin weren't seen as such by the clergy, so leeway was granted for the Metis to dance these dances and enjoy the music - as long as it wasn't overtly "Indian" in nature. This general prohibition against traditional native dancing and music, while at the same time condoning it in the European-style paved the way for the Metis to create their own dinstinctive dances and music to satisfy their need for Indigenous cultural expression by blending and blurring the lines. To be certain, the polkas, waltzes, quadrilles, reels, and jigs enjoyed by the Metis were essentially of European derivation with some Metis flair, but the most famous dance of them all - the Red River jig - uniquely featured a combination of Indian dance steps that made it stand out and become immensely popular. A fascinating explanation for the origins and Indigenous roots of the Red River jig are found in a short description given by Louis Goulet, a Montana Metis, recalling a dance/music session during the late 1800s: "During the feast there'd be a big singing contest and after that would come the dancing. Talk about every kind of reel and jig you can imagine! Fiddles, drums, accordions, guitars, Jew's harps and mouth organs, anything was fine as long as it went along more or less with the rhythm. At a shindig like that it was always a contest to see who could play the best, who could dance the best, who could sing the best, who could wear through his moccasins first, who'd be the first to cripple up with cramps in the legs. If the house had a wood floor, it would be creaking under the steady rhythm of dancing feet. If there was no floor, which was usually the case with those winter houses, the bare ground took all the stamping from our moccasins and the spectators were forced out many times in the evening for a breath of air because the dust inside would be suffocating. I often think the Red River Jig was invented one evening like that when sometimes the only instrument was an Indian drum. One night we were all jammed into Omichouche Godin's house in the Judith Basin on the Missouri River. The dance started. There was no wood floor and I don't remember any other instrument than an Indian drum. Some men were sitting on the ground around the drum, pounding away like mad to the rhythm of the Red River Jig while the dancing men and women took turns with wild enthusiasm. Spectators sat on the ground all around the room with their backs to the wall, almost completely invisible because of the dust and pipe smoke. The dancers kept time by clapping and snapping their fingers over their heads, adding an extra touch to the rhythm of their dancing feet. Broken by pauses when we sang, the dancing went on into the wee hours of the morning." Among the old-time Metis, just about any occasion was right for merry-making. The return to Red River from the annual summer buffalo hunt, New Year's Day, weddings, or just because were regarded as reasons for celebration and dancing. Even today, you cannot attend a Metis event or celebration without at least some jigging happening - usually the Red River jig! A general decline in the beaver fur trade between 1805 and 1821 resulted in cultural changes among the Cree, Ojibwe, and Métis populations around Red River settlement. Declining game populations and disenchantment with the state of the fur trade led to greater adoption of the horse and a focus on bison hunting. More and more often, Métis were working in cooperation with their Ojibwa and Cree relatives, and new bands formed which resulted in a blurring of the cultural and kinship divides between these groups. Because of the declining fur trade, these new multi-ethnic bands made adjustments to their seasonal subsistence patterns to compensate—diversifying their hunting activities and where they chose to live. Rather than return to Red River settlement each year, these groups were more often staying to the west in places like Wood Mountain, Riding Mountain, and the Cypress Hills over the winters. Trapping beaver became less important as the returns from bison hunting were more profitable in terms of valuable pemmican and hides. Cultural changes began to happen as well, with a blending of designs appearing in clothing, decorative beadwork, and other outward displays of material wealth. In 1820, Peter Fidler noted that many of the people he encountered were starting of decorate themselves in “very flashy” silver ornaments, necklaces made of wampum, arm and wrist bands with gorgets, broaches, and beadwork. More colors were used such as fancy leggings garnished with ribbons and beads, and other garish clothing items were employed to look (at all times) very “tastefully arranged”. With the merger of the Hudson's Bay and North West Companies in 1821, it was hoped that trade would increase for the new joint company. Unfortunately, new competition from the American Fur Company and independent traders cut into that hope. Many of the multi-ethnic bands took advantage of this and created new economic opportunities for themselves. Pembina became a more important location for both the Ojibwe and Métis, with many making it their new base of operations over Red River settlement. This shift away from Hudson Bay Company was accelerated by a refusal to offer credit and to withhold alcohol and other luxury items from the Indigenous hunters. The closure of some smaller trading posts also served to drive trade westward, and Fort Union became a new focus during the 1830s. These changes, combined with a rapid growth of the Métis population, led to a shift in the northern Plains power structure during this time. In 1821, there were only about 500 Métis living with their Ojibwe relatives at Pembina, but by 1830 there were over 1,300. This new “Pembina Band” began organizing large-scale bison hunts that set out each summer, and which stayed in the field until autumn. The huge scale of these hunts made this group powerful both economically and militarily. The large size of the main camp made them less vulnerable to enemy attacks, and because of this they could venture farther into Dakota territories to the south and west with little fear of reprisal. By the time of the 1863 Treaty at the Old Crossing, this territory extended to include the entire Red River Valley south to the Sheyenne River, and all of what is now northern North Dakota all the way west to Montana. While the Pembina Band finally lost prominence due to the forces of colonialism and the disappearance of the bison during the late 1800s, the band was able to rise to become one of the most powerful multi-ethnic groups on the northern Great Plains in less than a century. For more information, read: Peers, Laura L. (Laura Lynn). 1994. “Ojibwa Of Western Canada, 1780 To 1870.” Manitoba Studies In Native History. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

WALHALLA (ST. JOSEPH) A beautifully situated community located in the wooded river valley at the slope of Second Pembina Mountain, Walhalla (or Old St. Joseph) got its start when trader Norman Kittson built a trading post here in 1843 to take advantage of the many Ojibwe and Metis who camped here throughout the year. Antoine B. Gingras, a half-breed trader, also started a post here in 1843. Later, in 1848, Father George Belcourt established a mission here which was called St. Joseph to work with the 50+ families who made this their regular home. In 1851, additional missionaries arrived, and in 1853 the Pembina Belfry, known as the “Angelus Bell”, was relocated to St. Joseph to officially sanctify the mission. The bell is believed to have been brought from Pembina to St. Joseph by Red River cart. By 1860 the settlement had become an important fur trading post, with a population of 1,800—mostly Metis half-breeds and Plains Ojibwe. In 1862 a post office was established and it was a burgeoning town with a strong community. However, by 1870, the good furs became scarce in the rivers and streams of the Pembina hills, and the buffalo had virtually disappeared. By 1871, Walhalla was inhabited only by a priest, the U. S. customs inspector, and some 50 Metis people who had settled here (more or less) permanently. The town revived and was platted in 1877. It was renamed Walhalla by the Icelandic people who were settling in the region. Although most of the Metis inhabitants left the area, some families still remain in the area until today, and each year a festival is held at the Gingras Trading Post State Park. LEROY Originally known as Leroy’s Trading Post, Leroy was established as a Metis community during the 1850s. This post, on the Pembina River, consisted of several households of Metis log cabins scattered in the timber along the river. In 1873, Father LaFlock transferred the Saint Joseph Mission from Walhalla to Leroy to serve the Metis living here, and a post office was established in 1887. Over the decades, the town lost most of its inhabitants to out-migration and old age. The town is now a ghost town, with no census returns during the 2010 census. However, an interesting legend, or ghost story, does persist for Leroy. A road, known as White Lady Lane, goes through the Tetrault Woods between Leroy and Walahalla. Local legend tells of a young girl who became pregnant out of wedlock. Her religious parents forced her to marry the man against her will, and after the wedding, the baby died. The distraught girl hanged herself from a bridge, and her ghost has been seen hanging from the bridge in her wedding dress. The bridge is located down a narrow road off County 9. OLGA This small town, now nearly a ghost town, Olga was originally known as St. Pierre, due to the mission established by Catholic priest, Cyrille Saint Pierre, who was assigned as postmaster in 1882, but it was shortly thereafter renamed Olga in 1883. A small Metis community lived at this location, and it was a favorite camping ground for the Plains Ojibwe and Metis. During the 1800s, and a famous battle between the Ojibwe/Metis and Dakota Sioux—the Battle of O’Brien’s Coulee—took place about a mile from Olga in 1848. References:

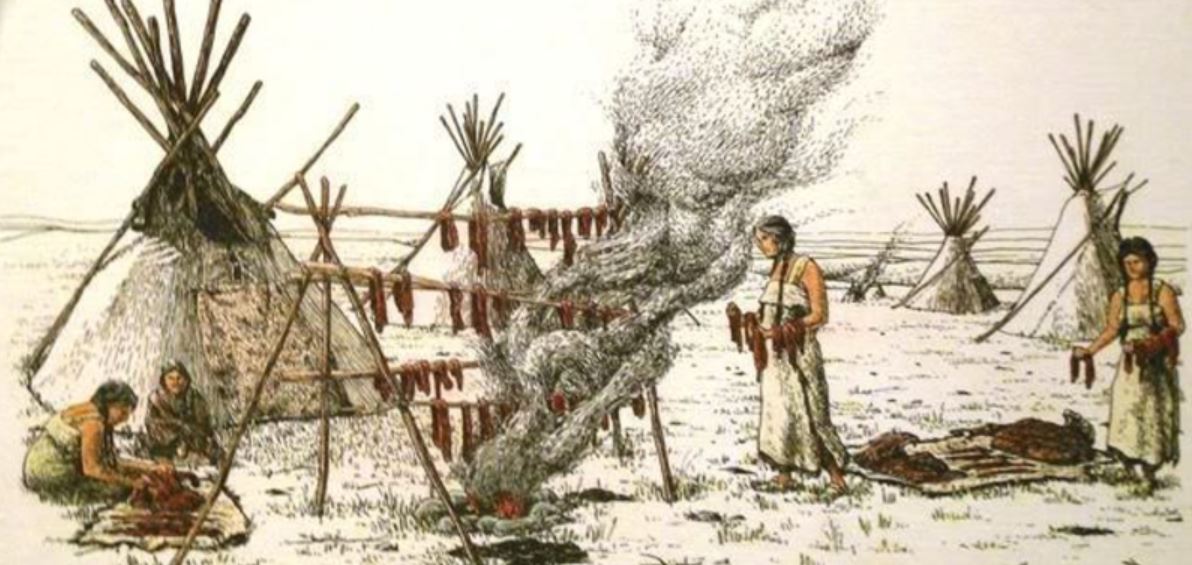

WPA Federal Writers Project (1935). North Dakota: A Guide to the Northern Prairie State. Washington: USGPO Barnes-Williams, Mary Ann (1966). Origins of North Dakota Place Names. Bismarck: Tribune Publishing By almost any account you read regarding the subsistence of the indigenous people of the prairies, it is indisputable that Pemmican was the favorite food of the Indians and the Metis. Pemmican can be made from the flesh of any animal, but it was usually made from buffalo meat. The process of making it was to first cut meat into slices, then to dry the meat either by fire or in the sun. Once the meat was dried, it was then pounded into a thick flaky “fluffy” powder. Once rendered down, the meat was put into large bags made from buffalo hides. To this, rendered, melted fat melted fat was poured. The quantity of fat was nearly half the total weight of the finished product, in a portion where for every five pounds of powdered meat, four pounds of fat would be poured. The best pemmican generally saw berries and sugar mixed in for flavor. Once complete, the whole composition formed a solid block that could be cut into portions for later use. Fish was also used to make pemmican. During sturgeon fishing, much of the sturgeon flesh was cured and stored for later use. This was made by drying and pounding sturgeon flesh into a powder, to which sturgeon oil and berries were added. This mixture was then packed into sturgeon skin bags, and used similar to bison pemmican. A person could subsist on buffalo (or fish) Pemmican in good times and lean. Pemmican, with its high fat content, provides a high calorie source of energy that is almost unrivaled. Thus, it was an important food throughout the year, but especially in winter because it stayed “fresh” almost forever and could be stored without worry for years without spoiling. Pemmican could be eaten when other foods were scarce, it could be used to stretch a meal, or it could be eaten on its own just like a block of fatty jerky – a great, portable source of food energy on long hunts or while doing any task where energy was needed. When cooked, Pemmican was easily turned into rubaboo (the most popular method by far) making a delicious stew that could feed an entire camp. Another method was to serve it fried – mixed with a little flour – to create a tasty roux that could be sopped up with bannock bread for a filling meal.

So what does pemmican taste like?' The only way you can describe the taste, is that it tastes 'Like pemmican.' There is nothing else in the world that bears the slightest resemblance. In terms of its quality as a food, it is a ‘super food’.

Before the introduction of modern medicine, the Kookums (Grandmothers) were the traditional keepers of knowledge of herbal plant remedies. They were midwives for the Anishinaabe community and had an understanding of a whole range of medicines that could cure illness that their families might encounter. This knowledge was not exclusive, but was something that was shared between First Nations women and their children, including the Métis.

This is why we must honor our grandmothers and our mothers, for they hold the wisdom and knowledge of generations of mothers and grandmothers before them. Once, a long time ago, a young man lived with his wife and children in a remote area near a large lake. He would go hunting every day and would return with all sorts of game.

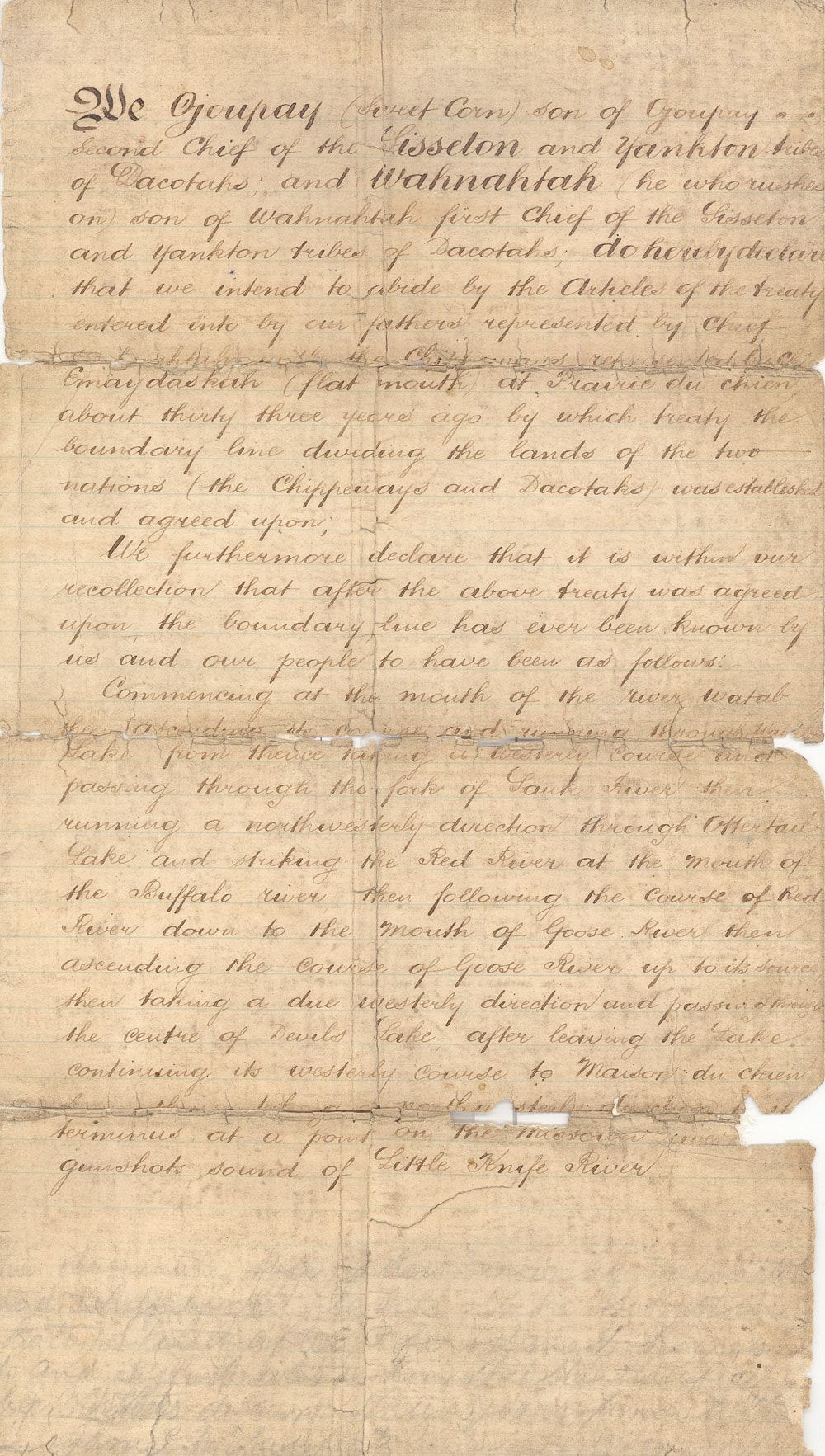

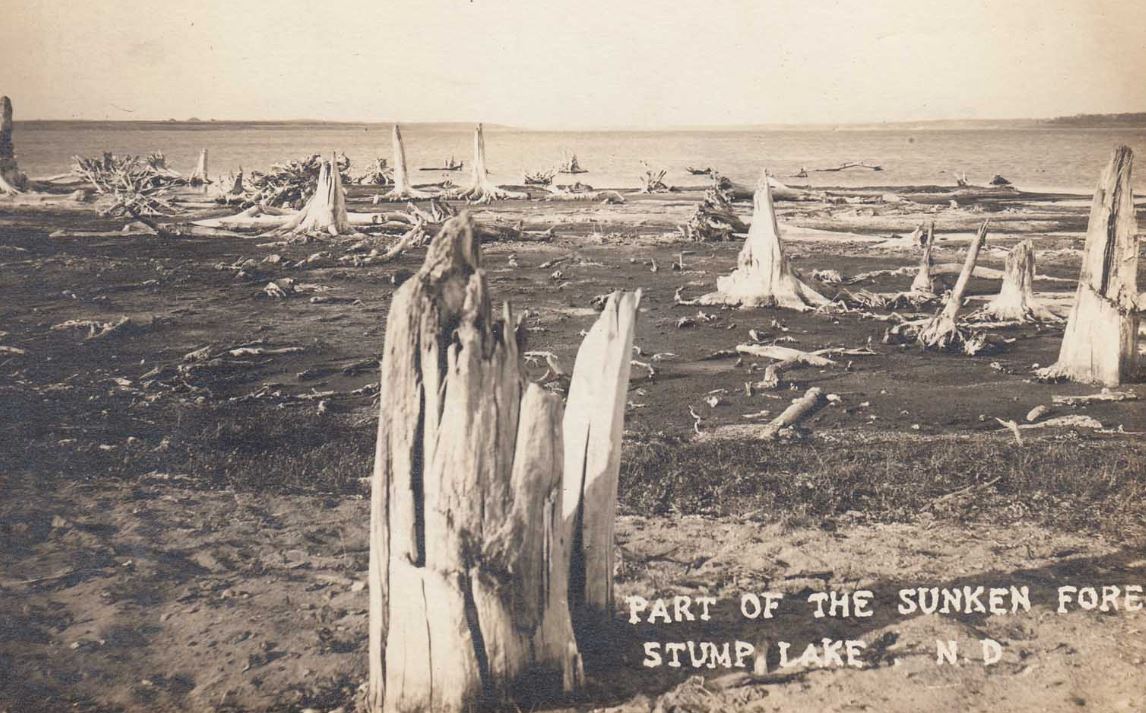

During one of his hunting trips, he saw a fat squirrel and shot it with his arrow. As he was going to pick it up, he noticed a small man about two feet tall coming from around a tree. The small man – a memegwesi – said to the hunter, “Beshwaji! I was stalking that squirrel for my prey. You stole it from me, but I do not hold a grudge for that. Nonetheless, could you give it to me so that I might feed my family?” The young hunter agreed, and he and the memegwesi decided to camp together, and they both had a great time sharing stories and boasting about their hunting prowess. After a successful time hunting, the young man asked the memegwesi if he would like to bring his family and live with him in his lodge. They could be brothers and always hunt together. The memegwesi agreed. The memegwesi had a wife and two young children: one was no bigger than six inches high, the other about one foot high. They came to the lodge of the young hunter and took up house in a corner of it. Every day the young man and the memegwesi would go out hunting. The young man might kill a deer or a moose, and the memegwesi would kill squirrels and rabbits. They had good luck every day, and when they would go home the memegwesi’s wife would help him bring his squirrel or rabbit inside and would cook it up for him, and the young man’s wife would cook his deer. The memegwesi’s wife would scrape the hides of his small animals and made him wonderful clothing. This little memegwesi had powers to do certain tricks, and he would entertain his family and the family of his young friend through the long winter nights and he would bring luck to his friend. They were all very happy in their friendship. One day during a particularly warm spring, just after they had made maple sugar together, the memegwesi told his young friend, “We are leaving now. We have had a good time living with you and thank you for always being my friend. I wish you good luck every day and to be happy all your life.” The memegwesi family gathered up their things and disappeared. Until his dying day, the young hunter and his family always had good luck thanks to his memegwesi friend’s blessings. By Kade Ferris One of the most reliable sources for defining the territory of the Pembina/Turtle Mountain Ojibwe in what is now North Dakota comes from the 1858 peace agreement, forged between the chiefs and headmen of the band and the Sisseton and Yankton Dakota, called the “Sweet Corn Treaty”. The Sweet Corn Treaty sought to establish peace and to define hunting and territorial boundaries so that there was no cause for warfare and so that resources would be shared without animosity. The Sweet Corn Treaty was read into various congressional bills throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, and was later used in the official findings of the Indian Claims Commission. The language of the treaty stated: We, Ojoupay (Sweet Corn, son of Ojoupay), second chief of the Sisseton and Yankton tribes of Dakotas, and Wahnatah (He-who-rushes-on), son of Wahnatah, first chief of the Sisseton and Yankton tribes of Dakotas, do hereby declare that we intend to abide by the articles of the treaty entered into by our fathers, represented by Chief Wahnatah with the Chippewas, represented by Chief Emaydaskah (Flat Mouth) at Prairie du Chine, about thirty-three years ago, by which treaty the boundary line dividing the lands of the two nations (the Chippewas and Dakotas) was established and agreed upon. We further declare that it is within our recollection that after the above treaty was agreed upon the boundary line has ever been known to us and our people to have been as follows: Commencing at the mouth of the River Wahtab, thence ascending its course and running through Lake Wahtab; from thence taking a westerly course and passing through the fork of Sauk River; thence running in a northerly direction through Otter Tail Lake and striking the Red River at the mouth of Buffalo River, thence following the course of the Red River down to the mouth of Goose River, thence ascending the course of Goose River up to its source; then taking the due westerly course and passing through the center of Devils Lake at Poplar Grove; after leaving the lake, continuing its westerly course to Maison du Chine [Dogden Butte]; from thence taking a northwesterly direction to its terminus at a point near the Missouri River within gunshot sound of the Little Knife River." (US Department of Interior 1872). This general territory was later granted congressional acknowledgement in an April 18, 1876, report of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, which after considering a memorial from the Turtle Mountain Chippewa, reported a bill that authorized the setting aside of a reservation for the Turtle Mountain Band. In its report the committee stated: The Turtle Mountain band of Chippewa Indians, and their forefathers for many generations, have inhabited and possessed, as fully and completely as any nation of Indians on this continent have ever possessed any region of country all that tract of land lying within the following boundaries, to wit: On the north by the boundary between the United States and the British possessions; on the east by the Red River of the North: on the south their boundary follows Goose River up the Middle Fork; thence up the head of Middle Fork; thence west-northwest to the junction of Beaver Lodge and Shyenne River; thence up Shyenne River to its headwaters; thence northwest to the headwaters of Little Knife River, a tributary of the Missouri River; and thence due north to the boundary between the United States and the British possessions (Indian Claims Commission 23-315). Just a few years later (September 25, 1880), Superintendent James McLaughlin, agent at the Devils Lake Agency, wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs concerning the plight of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa. He reported that white settlers were trespassing on their lands, and recommended that a reservation be set aside for them. Specifically, Agent McLaughlin reported: Inasmuch as the section of country west of the treaty line of 1863 running from Lake Chicot [Stump Lake] in a line nearly due west by Devils Lake and Dogs Den to the mouth of the Little Knife River on the Missouri, thence north to the "Roche Perce" or Hole in the Rock on the International line, thence east along the International line until its intersection with the treaty line of 1863, which tract is about 80 by 200 in extent, is recognized by all neighboring Indians as belonging to the Pembina and Turtle Mountain Bands of Chippewas, and as the same has never been ceded to the government, and the Indians being desirous to relinquish for a consideration to enable them to commence a life of agriculture, I would respectfully recommend it to the careful consideration of the Department (Indian Claims Commission 72-113). Each of the points mentioned in the above descriptions correspond to a place of importance and/or settlement associated with the Turtle Mountain Chippewa. For example, Stump Lake was the location of the village of Black Duck (Mug-a-dish-ib), a powerful sub-chief of the Ojibwe; Poplar Grove (Graham’s Island) is the location of the village of Chief Little Shell I and was also the location of a Chippewa village attacked by the Dakota in 1852; Dogden Butte was an important hunting and camping area to the Ojibwe (Indian Claims Commission 23-315). References:

United States Indian Claims Commission (ICC) (1970) Before the Indian Claims Commission. Indian Claims Commission Docket 23-315. United States General Printing Office. United States Indian Claims Commission (ICC) (1970) Before the Indian Claims Commission. Indian Claims Commission Docket 72-113. United States General Printing Office. US Congress (Department of Interior) (1872) U.S. Serial Set, Number 4015, 56th Congress, 1st Session, Pages 852 and 853. United States General Printing Office. |

AuthorKade M. Ferris, MSc

Archives

June 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed