Hereditary Head Chiefs ‘Aisance’ Little Shell I (b. ca.1756 – d. 1813)

Alternative Chiefs (appointed by the US)‘Misko-Makwa’ Red Bear (b. 1829 – d. 1879)

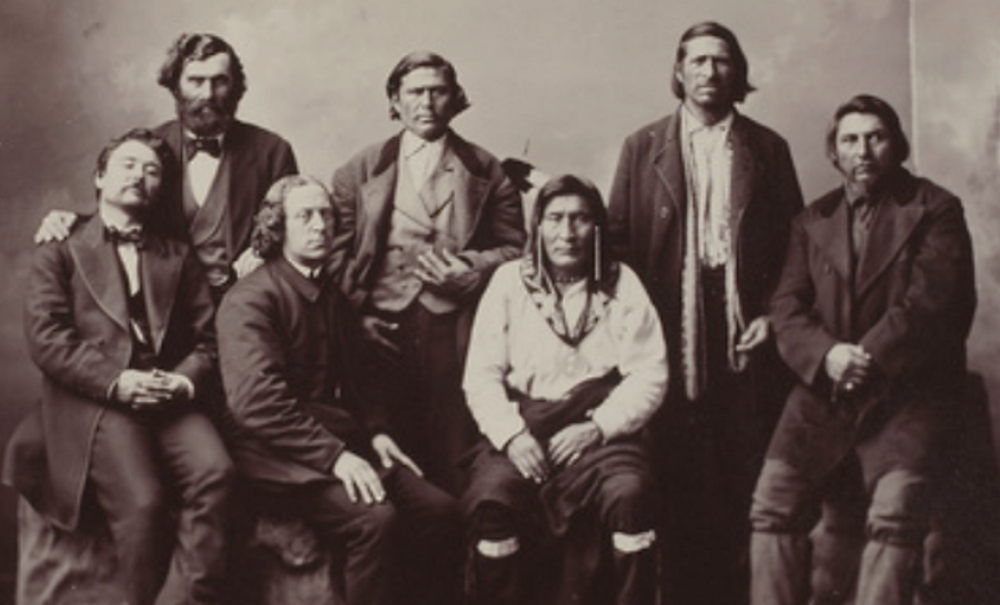

Half-Breed ‘Chiefs’ (Appointed by Maj. Wood in 1850)J.B. Wilkie (b. 1803 – d. 1886) J.B. Dumont (b. 1799 – d. 1884) Baptiste Vallee (b. 1810 - d. ???) Edward Harmon (b. ca. 1805 - d. ???) Joseph Laverdure (b. 1814 – d. 1888) Joseph Nolin (b. 1804 – d. 1872) Antoine “Labelle” Azure (b. 1794 – d. ???) Robert “Bonhomme” Montour (b. 1787 - d. 1857) Baptiste Lafournaise (b. 1815 – d. ???) Sub-Chiefs & Headmen'Mis-to-ya-be' Little Bull

Modern Chiefs'Kakenowash' Flying Eagle

3 Comments

Turtle Mountain Tribal Flag Turtle Mountain Tribal Flag The flags of North Dakota’s five tribal nations will be on permanent display outside the governor’s office at the state Capitol. Republican Gov. Doug Burgum announced the decision to display the flags during his State of the State address in January. The bipartisan Legislative Procedure and Arrangements Committee approved making the display permanent on Thursday. They represent the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation; the Standing Rock Sioux; the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa; the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate; and the Spirit Lake Nation. The relationship between North Dakota officials and tribes has been strained in the past, especially during protests three years ago against the Dakota Access pipeline near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation. Burgum says the tribal flag display was done “in the spirit of mutual respect.” https://www.newscenter1.tv/tribal-flags-on-permanent-display-at-north-dakota-capitol/  In about 1808, on the same day that the Dakota attacked the Ojibwe at Long Prairie (Minnesota) a large war party of Sisseton, Wahpeton, and Yankton attacked the Ojibwe village near Pembina, who were encamped under the leadership of Aise-ance (Chief Little Shell I). The battle was quite fierce and despite being outnumbered, the Ojibwe made a firm resistance and succeeded in forcing the Dakota away from their encampment and the women and children there. As the fight raged on, the oldest son of the Aise-ance was killed and his body was stripped on a large British peace medal. The Dakota warrior then held up the medal and made a great war cry, shaking the medal in defiance of the Ojibwe. Aise-ance, who had not noticed the death of his beloved son, turned and saw what had happened. With a blood-curdling cry he rushed forward into the midst of the gathered Dakota warriors and shot down the warrior holding the medal at point blank range! The shocked Dakota stepped back and Aise-ance proceeded to cut of the entire head of his enemy. He then shook the head at the terrified Dakota, retreated holding it up in triumph, and soon reached a secure shelter behind a tree. The Dakota were so awe-struck that none of them were able to raise enough courage to shoot at Aise-ance until he was back to safety. Aise-ance then rallied his warriors and they fought with unusual fierceness, soon routing the Dakota who started a general retreat despite still outnumbering the Ojibwe. After the battle was over, a young Ojibwe hunter named Tabushaw and his friend Bena headed out, against the advice of their families, and sought to ambush the Dakota in their retreat. The caught up to the Dakota and fired into their ranks. After shooting, Bena turned and ran back to Pembina, but Tabushaw stayed and continued to attack. He kept up the fight with the whole Dakota war party, but he soon was killed. Following the battle at Long Prairie and the defeat at Pembina, the Dakota was put into full retreat by the Ojibwe across the Red River territory. As a result, they were forced to withdraw westward of the Red River and far to the south of the Mississippi, Minnesota, and Sheyenne Rivers. From this point forward, the Ojibwe were in firm control of the rich beaver dams of the Red River valley and were able to start hunting buffalo west to Devils Lake with the half-breeds from the Settlement. References:

Warren, W. W., & Niell, E. D. (1885). History of the Ojibways, based upon traditions and oral statements. Saint Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. Holcombe, R. I. (2016). Compendium of history and biography of polk county, minnesota (classic reprint). Place of publication not identified: Forgotten Books.  In the spring of, 1860, Charles Grant was encamped with a party of Ojibwe and Metis hunters on the Mouse River. In the middle of the night, twelve horses were stolen. No trace of the horses could be found. Later that summer, a party of thirty-six Yankton Dakotas arrived at St. Joseph with the stolen horses for the purpose of returning them in honor of the Sweet Corn treaty. The delegation with the stolen horses arrived, opposite St. Joseph about two o'clock in the afternoon on June 10th; they immediately crossed the river to return them. Unfortunately a large party of Ojibwe warriors fired on the Dakota, who were in the act of entering J.B. Wilkie’s home to surrender the horses officially. Under fire, the Dakota took possession of the house, removed the "chinking" from between the logs, and returned fire. During the heart of the battle, Mule – the son of the Red Bear – was shot three times in an attempt to enter the house to end the stalemate. Once at the door, he struggled to his feet, but he was stopped at the threshold by one of the Dakota who cleaved his head through to the chin with an axe. The firefight lasted until midnight. A constant barrage of bullets was kept up between the Indians up until the very end. At midnight, the Dakota finally fled the house and rushed about two hundred feet to the river, and were compelled to wade across the river on foot. When the fighting stopped, six Ojibwe, three Dakota, and two Assiniboine were killed. Wilkie's daughter was severely wounded in the thigh by an arrow. The Sioux left behind them thirty-two horses, (in addition to the twelve stolen ones). The Ojibwe cut up the bodies of their foes and burned them. The Metis had refrained from taking any part in the fight and afterwards sent emissaries to the Dakota at Devils Lake to assure them they still honored the treaty. The Dakota accepted their peace, but promised that they would return to settle accounts with the Ojibwe in numbers like the mosquitoes. In response to this brazen escalation in hostilities, the US Congress appropriated $50,000 for the erection of a fort at Pembina River to help keep the peace. Source: July 12, 1861, (Page 6) of the New York Times: An Indian Fight.; BATTLE BETWEEN THE SIOUX AND CHIPPEWAS.

|

ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed